May 14, 2016; Revised November 25, 2016; September 30, 2019; October 26, 2019; January 11, 2020; April 6, 2021; September 10, 2022

Material World and Immaterial (Invisible) World

1. Our “human world” is made of two types of worlds:

▪The material world (rūpa loka) that we experience with the five physical senses. This is our familiar world with living beings and inert objects. This world has sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and body touches. For example, we experience sights via, “cakkhuñca paṭicca rūpe ca uppajjati cakkhuviññāṇaṁ,” where cakkhu viññāṇa is “seeing.” The other four sensory faculties have similar expressions; see, “Contact Between Āyatana Leads to Vipāka Viññāṇa.” [Here, paṭicca [paṭi + ca] means cakkhu and rūpa “getting together” or “making contact.”]

▪We can also recall our memories from the past and any future hopes/expectations that we have. Those are in the “immaterial world” we experience with our minds. It is also called the “nāma loka” or “viññāṇa dhātu.”

▪Here we use the phrase “immaterial world” (“nāma loka”) to describe those dhammā that can only be experienced with the mind VIA, “manañca paṭicca dhamme ca uppajjati manoviññāṇaṁ.” Those dhammā include concepts, memories, etc in addition to kamma bīja with energy; see below. [Here, paṭicca [paṭi + ca] means mana and dhamma “getting together” or “making contact.”]

▪Note that there are six types of dhātu. Five dhātus (pathavi, āpo, tejo, vāyo, ākāsa) are associated with the rūpa loka. The sixth, viññāṇa dhātu, is associated with the nāma loka.

2. Those two worlds co-exist. We experience the immaterial (invisible) world or the nāma loka with the mind.

▪There are many things that we cannot “see” but we know to exist. For example, we know that radio and television signals are all around us, but we cannot “see” them. We need special equipment like radios or TVs to detect those signals.

▪Those dhammā in the immaterial world are just like that. An organ (mana indriya) in the brain detects those dhammā. Scientists are not aware of that yet. They think memories, for example, are stored in the brain. They are not.

▪Those memories are in that immaterial world that co-exists with the material world. Just like a radio can detect those invisible radio waves, mana indriya detects those “unseen” memories (and kamma bīja that bring kamma vipāka.)

▪You may ask how can the mana indriya sort out all those different memories and uncountable kamma bīja from our past lives. Did you realize that there are numerous radio and TV signals in a major city? Just like a radio or a TV can sort out and detect those signals, mana indriya can detect various types of dhammā.

What Are Dhammā?

3. Dhammā are what we perceive with the mind with the help of the mana indriya in the brain. Dhammā include our memories in addition to kamma bīja (kamma bhava) that can bring vipāka.

▪Only those with iddhi (super-normal) powers can recall memories from past lives. However, some children can remember past lives; see “Evidence for Rebirth.”

▪But dhammā (plural) also includes numerous kamma bīja due to our past kamma (not only from the present life but from past lives.) They are not mere memories but have energies.

▪Those dhammā with energy (i.e., kamma bīja) are CREATED by our minds. Specifically, they are created in javana citta. For deep analysis, see “The Origin of Matter – Suddhaṭṭhaka.”

▪Einstein’s famous equation relates tangible matter and energy: E = m * c^2, where E is energy, c is the speed of light, and m is mass (amount of matter.)

▪Just like plant seeds can germinate and become trees, our kamma bīja (kamma seeds; bīja means “seeds”) can germinate in our minds and bring kamma vipāka.

Rūpa Can be Dense or Fine (Subtle)

4. Rūpa in Buddha Dhamma cannot be translated into English as “matter” or “solid objects.” As we discussed above, our kammic energies are “stored” in the immaterial world (viññāṇa dhātu) as very fine rūpa called dhammā.

▪Of course, the word “dhamma” (without the long “a”) refers to a theory or teaching, like in Buddha Dhamma. Only when used in the plural, dhammā refer to those fine rūpā detected with the mind (with the help of mana indriya.)

▪Therefore, those very fine rūpā are called “dhammā” They are “anidassanaṁ, appaṭighaṁ,” meaning they cannot be seen or detected by our five physical senses; see, “What are Dhamma? – A Deeper Analysis.” They include “kammic energies” that can bring vipāka at any time.

▪They bring vipāka when the corresponding dhammā contact the mana indriya and get passed down to hadaya vatthu. Since viññāṇa dhātu pervades the universe, dhammā (or kamma bīja) can bring vipāka anywhere in the universe.

5. The five physical senses detect “dense” rūpā in the material world. Such dense rūpā are ABOVE the smallest “unit of matter” in Buddha Dhamma, called suddhaṭṭhaka. (A suddhaṭṭhaka is a billion times smaller than an atom in present-day science). The 28 types of rūpa consist of these “dense types of rūpa”; see “Rūpa (Material Form).”

▪The fine rūpā are normally not called rūpa but dhammā to make the distinction. Dhammā are very fine rūpa which are at or below the suddhaṭṭhaka stage. They are the rūpa are grasped only by the mana indriya or dhammayatana: “anidassanaṁ, appaṭighaṁ, dhammayatana pariyapanna rūpaṁ.” For a more in-depth analysis, see, “What are Rūpa? – Dhammā are Rūpa too!.”

All Thirty-One Realms Share the Immaterial World

6. The immaterial world is like a fine fabric that connects all living beings. We cannot experience the immaterial world with the five physical senses (that we use to experience the material world.) All 31 realms share the immaterial world.

▪In the four realms of the Arūpa loka, “dense matter” formed by suddhaṭṭhaka is absent (except for the hadaya vatthu of the arūpa Brahmā). Beings in the arūpa loka (arūpāvacara Brahmā) experience only dhammā. They do not have any five physical senses and only have the mind (hadaya vatthu).

Click to open in pdf format: WebLink: PDF File: Two Types of Loka

▪Thus the “material world” is accessible only to living beings in the kāma loka and rūpa loka.

▪Arūpa loka means there are no “condensed rūpa” (like those in kāma loka and rūpa loka), but of course, dhammā are there (those arūpa beings can think and recall past events just like us).

▪Furthermore, even in the rūpa loka only fine and subtle matter exists. There are no “solid objects” like trees. If we visit a rūpa loka, we may not see anything with our eyes.

The World in Terms of Dhātu

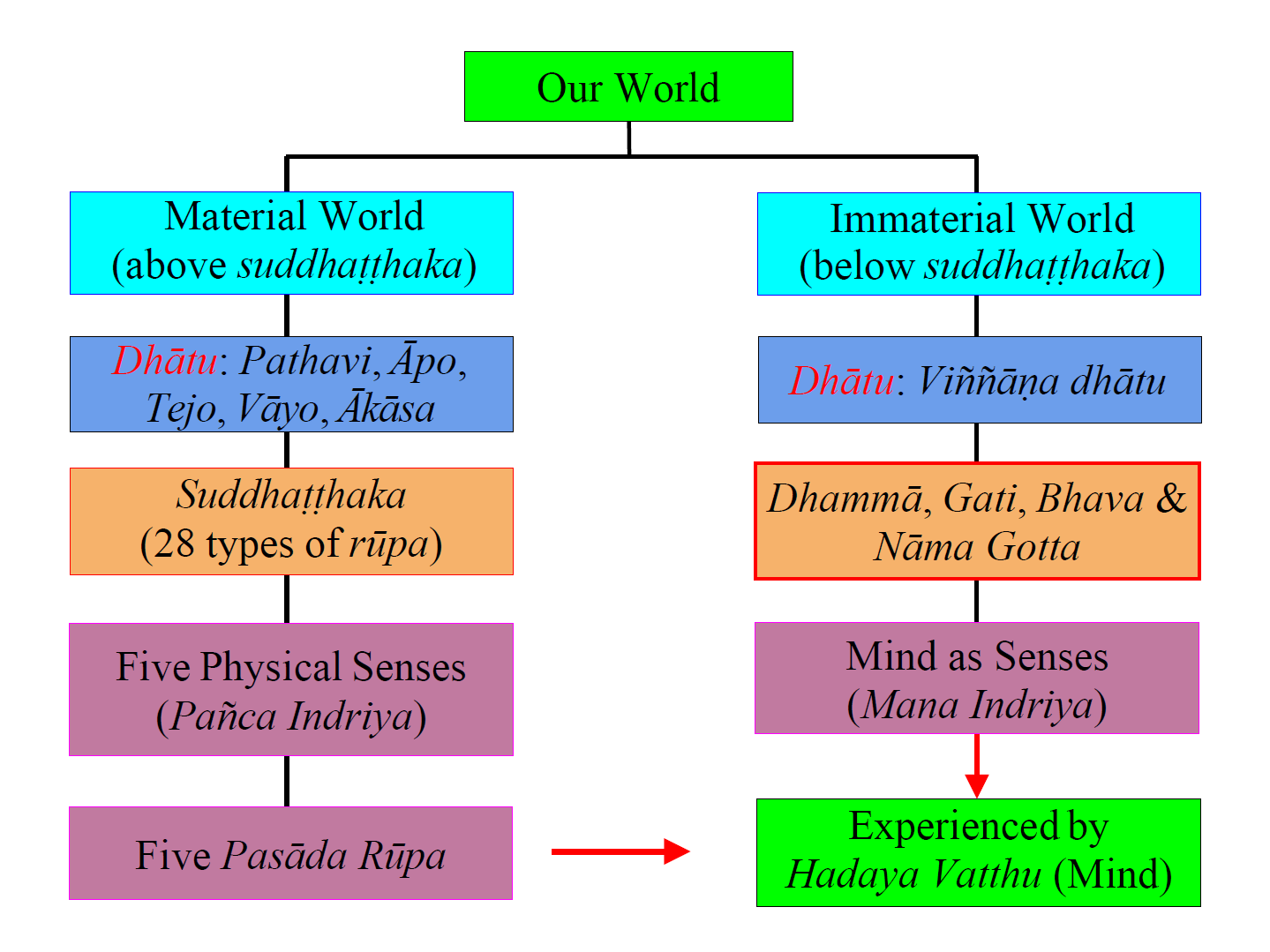

7. Let us briefly discuss the main points depicted in the above chart. Everything in this world is made of six dhātu: pathavi, āpo, tejo, vāyo, ākāsa, and viññāṇa. Five of them constitute the “material world” and the viññāṇa dhātu represents the “immaterial world.”

▪By the way, ākāsa is not merely “empty space.” We will discuss this later.

▪The basic building block for the material world is suddhaṭṭhaka. Not long ago, scientists thought that atoms were the building blocks, but now they say that even those elementary particles have structure. A suddhaṭṭhaka is much finer than any elementary particle.

▪In the immaterial world (or the mental plane), there are the mental precursors to suddhaṭṭhaka. They are dhammā, gati, and bhava. Based on our gati, we make suddhaṭṭhaka in our javana citta; see, “The Origin of Matter – Suddhaṭṭhaka.”

Five Physical Senses Detect Dense Rūpa and Mana Indriya Detects Dhammā

8. We have five sense faculties to experience the material world: eyes, ears, tongue, nose, and body. They pass down the sensory inputs to the five pasāda rūpa located in the gandhabba or the monomaya kāya, which overlaps our physical body); see “Gandhabba (Manomaya Kāya).” By the way, gandhabba is not a Mahāyāna concept: “Gandhabba State – Evidence from Tipiṭaka.”

▪On the mental side, we have a mana indriya in the brain to sense the immaterial world; see, “Brain – Interface between Mind and Body.”

▪Based on those five physical sense contacts with the material world and the contacts of the mana indriya with the immaterial world, our thoughts arise in the hadaya vatthu (also located in the gandhabba or the monomaya kāya); see, “Does any Object (Rūpa) Last only 17 Thought Moments?.”

▪That is a very brief description of the chart above. One could gain more information by clicking on the links provided and using the “Search” button. Don’t worry too much if all this does not make complete sense.

9. Thus it is important to understand that there are two types of rūpa in our human world:

▪Tangible matter in the material world that we experience with the help of the five physical senses.

▪Then there are unseen (anidassana), and intangible (appaṭigha) rūpa such as thoughts, perceptions, plans, and memories. They are dhammā, mano rūpa, gati, bhava, nāma gotta. It is the mana indriya in the brain that helps detect subtle rūpa.

▪ Both types of rūpa are eventually detected and experienced by the mind (hadaya vatthu). The hadaya vatthu is not located in the brain but the body of gandhabba and overlaps the physical heart region of the body; see “Gandhabba (Manomaya Kāya).”

▪Comprehending this “wider picture” may need a little bit of effort. The world is complex and much of the complexity is associated with the mind. The seat of the mind is not in the brain but the fine body (manomaya kāya) of the gandhabba.

The Dream World

10. Another part of our immaterial world is the dream world.

▪When we dream, we “see” people and material objects. But we cannot say where those are located. They do not have a physical location; they are in the immaterial plane. And we do not “see” those dreams with our eyes, but with the mana indriya.

▪When we sleep, our five physical senses do not function. But the mana indriya in the brain does. Scientists do confirm that parts of our brains are active during sleep.

▪What is experienced in Arūpa Loka is somewhat similar to seeing dreams. Of course, one can contemplate in the arūpa loka. However, one is unable to read or listen. Therefore, one cannot learn Tilakkhaṇa (anicca, dukkha, anatta) from a Noble Person. Thus, one is unable to attain the Sotāpanna stage of Nibbāna in the arūpa loka. But if one had attained the Sotāpanna stage before being born there, one can meditate and attain higher stages of Nibbāna.

Dense Rūpa for “Rough” Sensory Contacts

11. There is another way to look at our sense experiences. Living beings are attached to this world because they expect to gain pleasure from this world. Such pleasures are obtained by making contact with rūpa. Those rūpā come at various densities.

▪Bodily pleasures are achieved by the strongest contact (touch). Then come taste, smell, vision, and sounds, becoming less dense in that order.

▪The softest contact is via dhamma. This is our immaterial world; we think, plan for the future, remember things from the past, etc: We do this all the time, and we can do it anywhere. Another way to say this is to say that we engage in mano, vacī, and kāya saṅkhāra.

▪Thus, contacts by the mana indriya with dhammā in the mano loka constitute a significant portion of sense experience. That involves mano rūpa (dhamma, gati, bhava, nāma gotta) in the mind plane or the immaterial world.

12. The way a living being experiences and enjoys (or suffers) sense contacts is different in the three main categories of existence: kāma loka, rūpa loka, and arūpa loka.

▪Most “rough” or “olārika” sense contacts are available only in the kāma loka. Even here, they are roughest in the niraya (the lowest realm) and generally reduce in “roughness” as moving up to the human realm, the fifth. The six deva realms are significantly “softer” than the human realm; deva bodies are much finer (like gandhabba) and a normal human cannot see them.

▪The roughest sense contacts (touch, taste, and smell) are absent in the rūpa loka. Only visual and sound contacts are available for the Brahmā in the 16 rūpa loka realms, in addition to the mind.

▪Those arūpi Brahmā in the four arūpa loka realms has only the mind, with which they experience only the finest rūpa (dhamma) that are below the suddhaṭṭhaka stage.

▪Those Brahmā in both rūpi and arūpi loka have seen the perils of “kāma assāda” that are available in the kāma loka. They had enjoyed jhānic pleasures as humans and valued those more than the “rough” sensory pleasures. They have given up the craving for those “rough” sense pleasures that are available via touch, taste, and smell.

Stronger Cravings Match “Denser Sensory Contacts”

13. We can get an idea of such “soft” and “rough” sense contacts with the following example. Suppose someone (a grandmother is a good example) watches her grandchild laughing, dancing, and having a good time.

▪At first, she may be watching from a distance and enjoying the sight of the baby having fun.

▪Then she goes and hugs the child. It is not enough to just watch from a distance; she needs to touch the child.

▪If the child keeps wiggling and having a good time, the grandmother may start kissing the child. In some cases, the grandmother may start tightening the hold on the child, even without realizing it and may make the child cry out in pain.

▪This last scenario exemplifies how the craving for extreme sense pleasures can instead lead to suffering. Of course, the craving for oḷārika sense pleasures leads to most suffering.

▪But suffering is there even in the rūpi and arūpi realms. Even at the level of arūpi Brahmā — where the attachment is only to pleasures of the softest of the rūpa (dhamma) —, there is inevitable suffering at the end when they have to give up that existence and come back down to the human realm.

Less Suffering in “Less-Dense” Realms

14. Therefore, the level of inevitable suffering goes hand in hand with the “denseness” of the sensory contact.

▪Pains, aches, and illnesses are there only in the lowest five realms (including the human realm) where there are dense physical bodies. In the higher realms, those are absent. This is the price even humans pay for being able to experience “rough contact pleasures” such as a body massage, sex, eating, and smelling.

▪We humans in the kāma loka enjoy close and “rough” sense pleasures. In addition, most times, just enjoying sense pleasures is not enough; we like to “own” those things that provide sense pleasures. For example, people like to “own” vacation homes; it is not enough to rent a house in that location just for a visit.

▪This tendency to “own” pleasurable things also goes down in higher realms. There are fewer material things to “own” in Brahma lokas, especially in the arūpi Brahma realms.

Connection to Magga Phala

15. As one attains higher stages of Nibbāna, craving for “rough” sensory pleasures and the desire to “own” things go down.

▪A Sotāpanna has only “seen” the perils of kāma assāda; he/she still enjoys them. Thus, he/she will still be born in the kāma loka realms, but not in the apāyā.

▪A Sakadāgāmī may still enjoy “kāma assāda,” but has no desire to “own” those things that provide pleasures. It is enough to live in a nice rented house, and there is no desire to own a nice house. A Sakadāgāmī can see the burden of “owning things.” A Sakadāgāmī will be born only in realms above the human realm.

▪An Anāgāmī has no special interest in enjoying kāma assāda. He/she eats to quench the hunger (but will eat delicious foods when offered.) An Anāgāmī will never prioritize sensory pleasure over the “pleasure of Dhamma” (of course, Dhamma here means Buddha Dhamma). He/she will be born in the rūpa realms reserved for the Anāgāmīs upon death, and will not be reborn in kāma loka.

▪An Arahant has no desire for even jhānic pleasures, and will not be born anywhere in the 31 realms upon death.

16. Each habitable planetary system (cakkavāla) has all 31 realms of existence, even though we can only see two realms (human and animal) in ours.

This is discussed next: “31 Realms Associated with the Earth”, ………