April 22, 2016; revised September 22, 2019; #17 added March 31, 2021; March 6, 2023; July 8, 2024

The brain is Not the Mind

1. Contrary to what scientists believe, our minds are not in the brain (this is another prediction from Buddha Dhamma that will be proven correct in the future).

▪The “mind door” where citta (or thoughts) arise is at the hadaya vatthu, which is not in our physical bodies. It is in the manomaya kāya of the gandhabba; see “Gandhabba (Manomaya Kāya)- Introduction.”

▪The gandhabba has a subtle body; it is not a “body” in the sense we usually think about a “body.” It is more like an energy field that overlaps the physical body; see “Ghost in the Machine – Synonym for the Manomaya Kāya?.”

▪The hadaya vatthu overlaps the heart in the physical body. When we hear traumatic news, we feel a burning sensation close to the heart, not in the head. We don’t say, “Oh, my head felt burning when I heard the news.” It is the heart area that feels it. (The head may start hurting later if one keeps thinking about the loss).

▪On the other hand, when we overuse our five physical senses or think hard about a complex problem, our heads hurt. That’s because the brain has to do a lot of processing in those situations. While watching a movie, our brains work overtime to convert sensory inputs from the eyes (cakkhu indriya) and the ears (sota indriya). When we think about a complex problem, the brain’s mana indriya must work hard; see below.

Two Overlapping “Bodies” – Physical Body and Gandhabba (Mental Body)

2. A physical body is a temporary shelter or a “shell” for the gandhabba’s subtle body. The gandhabba receives sense inputs from the outside world via the physical body. See “Body Types in Different Realms – Importance of Manomaya Kāya.”

▪Since a given physical body has a lifetime of around 100 years, we have to “build a new physical body” when the current one decays and finally dies. (That is if we have extra kammic energy for the human bhava); see, “Bhava and Jāti – States of Existence and Births Therein.”

3. Before entering the mother’s womb, the gandhabba has an invisible “body,” more like an “energy packet.” Thus, it cannot experience taste or touch, even though some can “digest odors” and become denser.

▪A gandhabba waiting for a womb is usually about the size of a fully-grown human, but it has very little “matter” that is not visible to us. At the moment of “okkanti” or entering the mother’s womb, he/she will enter through the mother’s body and collapse to the size of the zygote when taking possession of it; see, “Buddhist Explanations of Conception, Abortion, and Contraception.”

▪Thus a gandhabba, when outside waiting for a suitable womb, is just like a ghost shown in the movies. Of course, humans cannot see it even with technological advances. It is much smaller in mass than the first cell formed by the union of the mother and father, the zygote.

▪The physical body grows to start with a single cell (zygote) using the nutrition from the mother. After the baby is born, it consumes food to grow to the size of an adult.

▪Thus it is helpful to have this visual, where a very fine gandhabba trapped inside a physical body of over a hundred pounds controls it.

Brain – Interface Between the Physical Body and Gandhabba

4. Once inside a physical body, gandhabba has to use the physical body to interact with the outside world. It is like being trapped in a solid shell. Initially, its mind will be in the bhavaṅga state (see, “Citta Vīthi – Processing of Sense Inputs”) and not conscious of the outside world, except for body sensations.

▪In a human, the brain first processes the signals coming through the “physical senses” (eyes, ears, etc.). The brain transmits that information to the five pasāda rūpa in the gandhabba. Those pasāda rūpa then pass that information to the hadaya vatthu (seat of the mind) in the gandhabba; see, “Gandhabba (Manomaya Kāya)- Introduction.”

▪That is how our minds receive information from the external world.

▪Now the question arises: “How do the sense inputs coming through the eyes, ears, tongue, nose, and body are transmitted to the pasāda rūpa (situated close to the hadaya vatthu)?.” Note that the hadaya vatthu overlaps the physical heart.

5. The brain acts as the intermediary between those physical sense inputs and the five pasāda rūpa. It processes incoming information and converts it to a form that can be understood by the mind (hadaya vatthu).

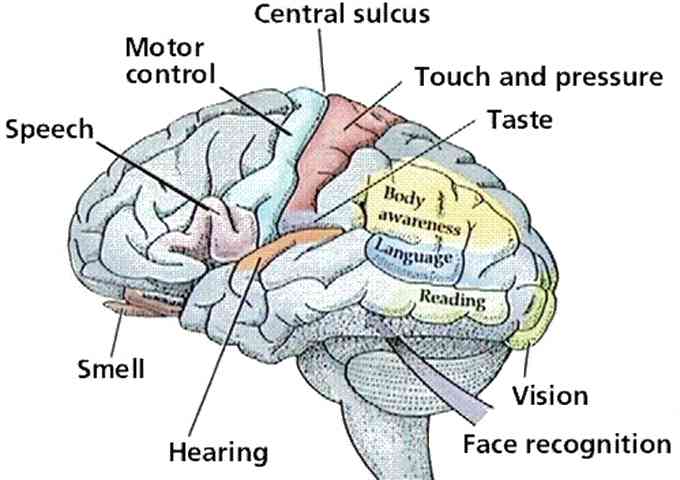

▪First, the sensory inputs coming into the physical body through the eyes, ears, tongue, nose, and body go to specific brain regions. That has been well-researched by scientists over the past hundred years. The following figure shows the specific areas of the brain that analyze the data from the five senses.

Brain and five Senses

▪Science cannot explain how the brain comprehends the corresponding signals after processing those signals. For example, in vision, there is no “picture” formed in the back of the head; see “On Intelligence” by Jeff Hawkins (2005) for a helpful discussion.

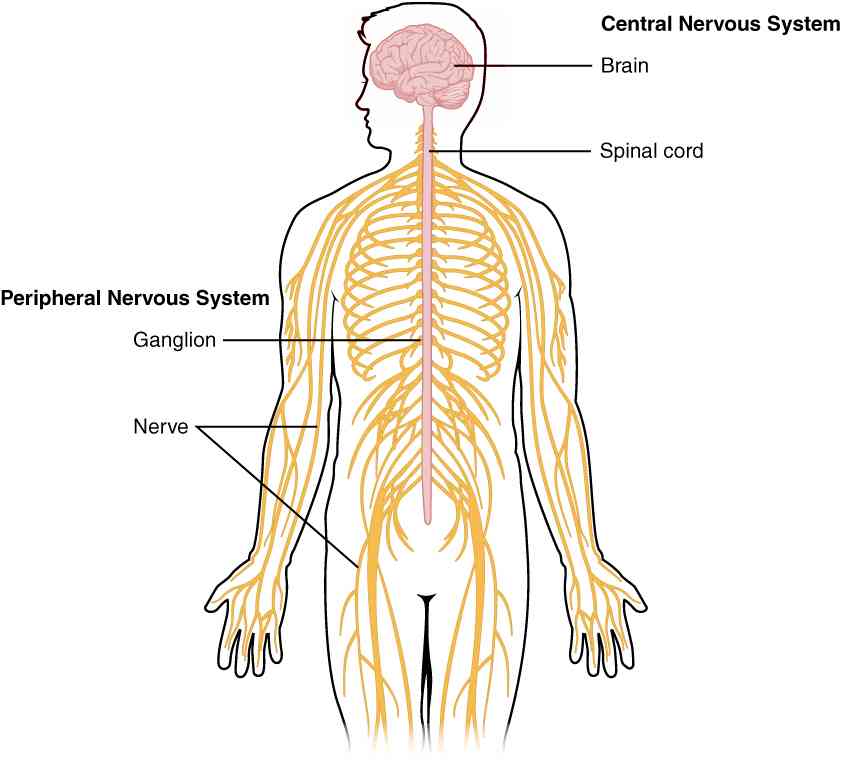

6. The signals for vision, sounds, smells, and taste come into the body through specific body parts. In contrast, the touch sensations can come from anywhere in the body and transmitted to the brain via an intricate system of nerves:

Nervous System

▪These nerve signals go to the brain for processing (see the “touch and pressure” processing area in the figure on #5 above).

Gandhabba (Mental Body) Overlaps the Physical Body

7. It is essential to note that the misty gandhabba has a similar “nervous system” that overlaps the physical nervous system shown above. Yes. Gandhabba is more like an “energy field.” (This is irrelevant to the present discussion, but the physical body imparts kamma vipāka via body aches, diseases, and injuries.)

▪The physical nervous system has to align with the nervous system of the gandhabba. That alignment could change (due to kamma vipāka), which makes our body’s nervous system go out-of-alignment for proper body function, leading to aches and pains. See, #6 of “11. Magga Phala and Ariya Jhānā via Cultivation of Saptha Bojjhaṅga.”

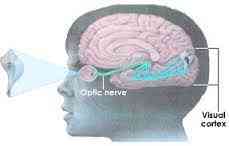

8. The signals from the other four senses go to specific brain areas (indicated in the figure of #5 above) via specialized neural pathways. For example, the optical nerve carries the visual signal to the brain:

Eye Indriya

▪Once the brain processes those sensory inputs from the five physical senses, they are “transmitted” to the corresponding five pasāda rūpa in the gandhabba (manomaya kāya.) See below.

Mana Indriya in the Brain

9. So far, we have identified five of gandhabba’s “windows to the outside world” from his/her “shell” or the physical body: eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and the body.

▪What about the “dhammā” that are the finest rūpa (mano rūpa) that interact with the physical body? That is how we think about “random things” out of the blue. For example, we may be washing dishes in the kitchen, and thoughts about a friend or a relative may come to mind.

▪Thoughts about a friend — who may be a thousand miles away — come through the mana indriya in the head (inside the brain). Of course, science is not aware of that.

▪We discussed this in a previous post: “What are Dhammā? – A Deeper Analysis.”

10. How are the signals processed in the brain due to incoming vision, sound, smell, taste, touch, and dhamma passed to the five pasāda rūpa and the hadaya vatthu?

▪The manomaya kāya has a blueprint of the physical body. The physical body grows according to that blueprint. As the physical body grows, manomaya kāya (also called a “kiraṇa kāya” because it is a subtle body, essentially the gandhabba) also “expands.” The brain in the physical body overlaps “the brain” in the manomaya kāya and transfers the processed information on sensory inputs to “the brain” in the manomaya kāya. The hadaya vatthu thus receives that information via the manomaya kāya.

▪It would be the reverse process when the hadaya vatthu sends commands to the brain, for example, to move body parts.

▪Further details in “Gandhabba (Manomaya Kāya)- Introduction.”

The Origin of Citta Vīthi

11. When information comes to one of the five pasāda rūpa, it passes on that signal to the hadaya vatthu by impinging (hitting) the hadaya vatthu. That results in the hadaya vatthu vibrating 17 times, just like a clamped blade, when hit by an object, vibrates a certain number of times; see, “Gandhabba (Manomaya Kāya) – Introduction” and “Citta Vīthi – Processing of Sense Inputs.”

▪That is the origin of a citta vīthi of 17 citta. Each citta in a citta vīthi corresponds to a single vibration of hadaya vatthu. This 17 thought-moment time is the lifetime of a hadaya rūpa (vibrational energy) of the hadaya vatthu.

▪It is a common mistake to take this to mean that any rūpa has a lifetime of 17 thought moments. That is a terrible mistake; see, “Does any Object (Rūpa) Last only 17 Thought Moments?.”

▪Describing these details in one or even several posts is impossible . One may need to look through other posts to clarify some concepts. The “Search” button on the top right is an excellent resource for this task.

12. Any of the five pasāda rūpā has to strike the hadaya vatthu to pass on its signal. However, signals from the mana indriya can exchange information with the hadaya vatthu directly.

▪When the mana indriya interacts with the hadaya vatthu, that also results in a citta vīthi; such manodvāra citta vīthi do not have a fixed length.

▪Still, only one of the six sensory signals can contact the hadaya vatthu at a given time. But since the process is swift, billions of citta vīthi can run through the hadaya vatthu “in the blink of an eye.”

Two Inter-Dependent “Bodies”

13. Therefore, this process involves interaction between two overlapping systems: the physical body and the corresponding subtle “energy body” of the gandhabba.

▪When the gandhabba escapes from the body under stressful situations, it can float above the physical body. Then the physical body becomes inert until the gandhabba returns to it; see, “Manomaya Kāya and Out-of-Body Experience (OBE).”

14. Thus, the brain plays a significant role in shaping our future. Similarly, the five physical senses play vital roles too.

▪If one of the five physical senses is damaged, we lose the corresponding “window to the external world.” We will not be able to see If both eyes are damaged. If the sensors inside the ears are damaged, we cannot hear, etc.

▪But the most critical is, of course, the brain. If the brain is damaged, sensory signals cannot be processed, and we cannot interact with the external world. Thus, being brain-dead is virtually equivalent to being dead.

▪However, if one’s brain becomes damaged due to an accident, it will not affect the gandhabba inside. It is just that the gandhabba will not be able to communicate with the external world. And if damage to the brain results in the death of the physical body, the gandhabba will just come out of the dead body and wait for a suitable womb.

Next Existence Determined by Gati and Kamma Vipāka

15. It does not matter whether one gets killed due to an accident or dies due to an illness or old age. The gandhabba’s future is determined by his/her gati (or gathi), past kamma (kamma bīja), etc.

▪If the physical body dies in an accident, the gandhabba will immediately come out of the dead body. Then it will wait for a suitable womb if there is still more kammic energy left for the human bhava (in an accident, that is likely).

▪But if one gets to old age and dies or dies due to illness — and if one has exhausted kammic energy for the human bhava — then the cuti-paṭisandhi will occur. If one is to become a deva, a deva will appear instantaneously in the corresponding deva world. If one is to become an animal, an animal gandhabba will emerge from the dead body and will have to wait for a suitable womb to become available.

16. It is also clear why we must take good care of the body, our sense faculties, and our brains. Gandhabba’s (our) ability to make decisions depends on all those faculties working in optimum conditions.

▪We have a short lifetime of around 100 years to get rid of our defiled (immoral) gati. We also need to cultivate good (moral) gati, comprehend the true nature of this world (anicca, dukkha, anatta), and be free from future suffering.

▪We need to try to get to the Sotāpanna stage of Nibbāna and be free from the four lowest realms (apāyā). At least, we must make progress towards that goal so that in a future life, we will have a tihetuka birth that makes it easier to attain Nibbāna.

▪We need to eat, exercise, and care for our bodies to perform optimally to accomplish those things. We also need to avoid drugs and alcohol and associate with those who have similar goals (and avoid those with bad habits).

17. Some scientists and philosophers are beginning to understand that memories are not stored in the brain. See, “WebLink: getpocket.com: The Empty Brain.”

Thanks to reader Diogo Roberto R. Freitas for alerting me to the above article.