December 5, 2023; revised March 29, 2025

Mūlapariyāya Sutta (MN 1) describes the “The Root of All Things” in this world. Here, I will clarify and point out the astonishing truth about our “built-in” distorted perceptions described in the sutta in simple English (however, a background in necessary concepts is required.)

Introduction

1. The “WebLink: suttacentral: Mūlapariyāya Sutta (MN 1)” embeds one of the critical “previously unheard teachings” of the Buddha.

▪The word-by-word English translation of the sutta in the above link makes it appear like a Zen reading, a riddle.

▪In this post, I will explain a “previously unheard astonishing concept” embedded in this first sutta of the Majjhima Nikāya of the Sutta Piṭaka.

▪First, I will provide the necessary background material with references. Please read those references AFTER going through the post. Then, one should re-read this post after grasping the background concepts.

Categorizing Births in Different Realms – Gati

2. Rebirths among the 31 realms in this world can be characterized in several ways. What matters the most is one’s gati (loosely translated as moral/immoral character) when grasping a new rebirth in a new realm.

There are five primary categories of gati, as stated in the “WebLink: suttacentral: Gati Sutta (AN 9.68)”: Nirayo, tiracchānayoni, pettivisayo, manussā, devā.

▪The main point is that three of the five gati lead to rebirth in the apāyās, i.e., the lowest four realms with the highest suffering. These are “immoral gati.”

▪Deva gati leads to rebirths in all higher realms (six Deva and 20 Brahma realms.) These are “moral gati.“

▪The human realm lies in the middle, and manussa gati can be moral or immoral. We have the ABILITY to cultivate either gati. In most cases, the external environment plays a huge role in that. For example, those born into “families with moral or immoral gati” will likely develop the corresponding types. A clear example is that a child born into a family of drug users/dealers is highly likely to develop an immoral character.

▪However, those fortunate to associate with others with “moral gati” can change their gati for the better and vice versa.

Human Realm – “The Training School”

3. The ability to cultivate/discard various types of gati is impossible in the four lowest realms and certain Brahma realms.

▪Furthermore, in the Deva or Brahma realms, the tendency is to enjoy life mostly free of suffering. There is no incentive to “cultivate moral gati.” Even among humans, those who are wealthy and healthy do not worry about these issues. Thus, being born wealthy and healthy could be a disadvantage!

▪That is why the human realm is special and unique. Since one can see both suffering and sensory pleasures, one can see the necessity of cultivating “moral gati.” Furthermore, the presence of a physical body with a brain slows down the “reaction time” and makes it possible to be “mindful” and “control oneself.”

▪The human realm can be compared to a “training school” where one prepares for the next birth. Those who cultivate “moral gati” TEND to be reborn in the “good realms” and others in the “bad realms” or the apāyās.

▪As explained in “Buddhism and Evolution – Aggañña Sutta (DN 27),” all those living beings in realms below the Ābhassara Brahma realm are reborn automatically in the human realm after the Earth is reformed. With time, they are reborn in apāyās to higher realms according to the gati they cultivate. However, at the end of their lives in the higher realms, they return to the human realm, and only a tiny fraction of them again return to higher realms. Most of those in the apāyās need to wait until the end of this Earth and the reformation of a new Earth to be born human!

Categorizing Births in Different Realms – Three Types of Loka

5. Another categorization is based on the number of sensory faculties. That places the 31 realms into three categories: kāma loka, rūpa loka, and arūpa loka.

▪When born in the kāma loka, one would have all six senses and will sense the world with seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, touching, and the ability to think about all those. The three sensory faculties of tasting, smelling, and touching require a dense physical body. While that provides access to the “pleasure of eating, smell, and physical touch (including sex).” that also makes it vulnerable to suffering via injuries and sicknesses. (One exception is that the Devās in the six Deva realms have “less dense” physical bodies not subject to injuries or illnesses.)

▪Therefore, some humans become dissatisfied with sensory pleasures (i.e., lose kāma rāga), cultivate anariya jhāna, and enjoy “less stressful jhānic pleasures.” They have temporarily given up “pleasures associated with eating, smelling, and sex.” Thus, they cultivate one version of “deva gati” and are reborn in Brahma realms.

▪Those in the rūpa loka are rūpāvacara Brahmās with three sensory faculties: seeing, hearing, and thinking. Since they don’t need physical bodies to be able to eat, smell, or touch, they don’t have even “finer physical bodies” like the Devās in the six Deva realms. They essentially have two pasāda rūpa (cakkhu and sota) and a hadaya vatthu where thoughts arise. Those are three suddhaṭṭhaka, billions of times smaller than an atom in modern science. That is hard even to visualize!

▪Some of those human yogis transcend the anariya jhānās and cultivate arūpa samāpatti. They are reborn in the arūpa loka, where only the mind (i.e., the hadaya vatthu) is present. They can only think, and most of the time, their minds are focused on the space or viññāṇa.

6. The main point I want to convey is the following. We were born in the kāma loka because when we grasped this existence, we had “kāma gati,” or highly-valued sensory experiences of taste, smell, and touch.

▪Those who valued kāma gati to such an extent that they engaged in highly immoral deeds to experience them have now been born in the apāyās. They had “apāyagāmi gati” that made them grasp rebirths in the apāyās.

▪Then, some saw the drawbacks of close-contact sensory pleasures and cultivated anariya jhāna/samāpatti. They will be born in the Brahma loka.

▪Each of us has done ALL OF THAT in our past lives, extending to an untraceable beginning. Each of us had been born in all 31 realms other than those reserved for the Anāgāmis.

▪We all had unbroken “mental bonds” or “saṁyojana” to the rebirth process. The possibility of rebirth in any realm can be permanently removed by breaking those ten saṁyojana one or more at a time.

Categorizing Births in Different Realms – Saṁyojana

7. Thus, we can use another helpful categorization is “saṁyojana,” or “bonds in the rebirth process.” There are ten types of saṁyojana.

▪A puthujjana (average human) has all ten saṁyojana. They can be reborn in any realm (other than those Brahma realms reserved for the Anāgāmis.) Grasping a new birth depends ONLY on the gati at that time, as discussed above.

▪Upon hearing the explanations of the “wider worldview of the Buddha,” one may start seeing the danger of remaining in the rebirth process, i.e., see the “anicca nature” of worldly pleasures.” That is when one becomes a Sotāpanna and removes three of the ten saṁyojana from the mind. At that point, rebirths in the apāyās will be stopped permanently. That means one will never be able to maintain/cultivate “apāyagāmi gati” or “highly immoral gati” that may allow the mind to grasp a rebirth in an apāya.

▪Thus, saṁyojana are not “physical bonds” but “mental bonds” rooted in the mind. The breaking of one or more saṁyojana happens with knowledge/wisdom about the fundamental nature of the world. It is somewhat like giving up alcohol once the destructive consequences of being an alcoholic are understood without a doubt. But while some alcoholics may go “backward,” a Sotāpanna Anugāmi (one of the eight types of Noble Persons) will never go back.

The Process of Breaking Saṁyojana – Way to Nibbāna

8. As you can see, there is a step-by-step way to remove those ten saṁyojana.

▪The first three (sakkāya diṭṭhi, vicikicchā, sīlabbata parāmāsa) are removed at the Sotāpanna stage. This requires a basic understanding of the fruitlessness and dangers of remaining in the rebirth process. That stops future rebirths in the lowest realms of kāma loka, i.e., the apāyās.

▪The next step is to stop rebirths at the next level, those in the human and the six Deva realms. That requires a deeper understanding of the “anicca nature.” The main point that I tried to convey above is the following: As long as we have a craving for the sensual pleasures available in kāma loka (i.e., kāma rāga), we will be reborn in the kāma loka. Thus, even a Sotāpanna will be reborn in either the human or one of the six Deva realms in the future UNTIL the two saṁyojana of kāma rāga and paṭigha are removed from the mind. (Paṭigha arises due to kāma rāga, i.e., when one does not get their way to enjoy such pleasures, paṭigha or anger arises.)

▪The higher five saṁyojanās keep one bound to the rūpa and arūpa loka (the 20 realms in the Brahma loka.) The same procedure we discuss below applies to removing those higher saṁyojana (as well as the first five saṁyojana).

▪The Mūlapariyāya Sutta explains a deeper, more fundamental reason why we are trapped in the rebirth process (in any realm.) It is a fundamental concept in Buddha Dhamma, thus the name Mūlapariyāya (the root of all things.)

The “Previously Unheard” Teaching of the Buddha

9. We were born in various realms at different times because we had the corresponding gati matching those particular realms at that time.

▪When we are born in a particular realm, we are born with the gati matching that realm. That should be clear since — as discussed above — we had grasped the rebirth in that realm BECAUSE we had that particular gati.

▪Those “birth gati” are embedded in the mind until another existence (in another realm) is grasped. In technical terms, those “birth gati” are in the “bhavaṅga state” of the mind. Let me explain the “bhavaṅga state” simply by considering an analogy of a car.

▪Consider a started car with a gear in the neutral position. It is not moving but “alive.” To be active (i.e., to move), it must be put on a gear to engage the wheels. In the same way, when a human is inactive (while sleeping, for example), they are not actively involved with an “active mind.” This “neutral state” of the mind is the “bhavaṅga state.” When a sensory input comes in, the mind switches to the active state where it examines that sensory input (and may take appropriate action.)

10. There is a detailed and precise process by which a mind switches from the “bhavaṅga state” to the active state. A basic understanding of this is essential, even though learning the detailed Abhidhamma description is unnecessary.

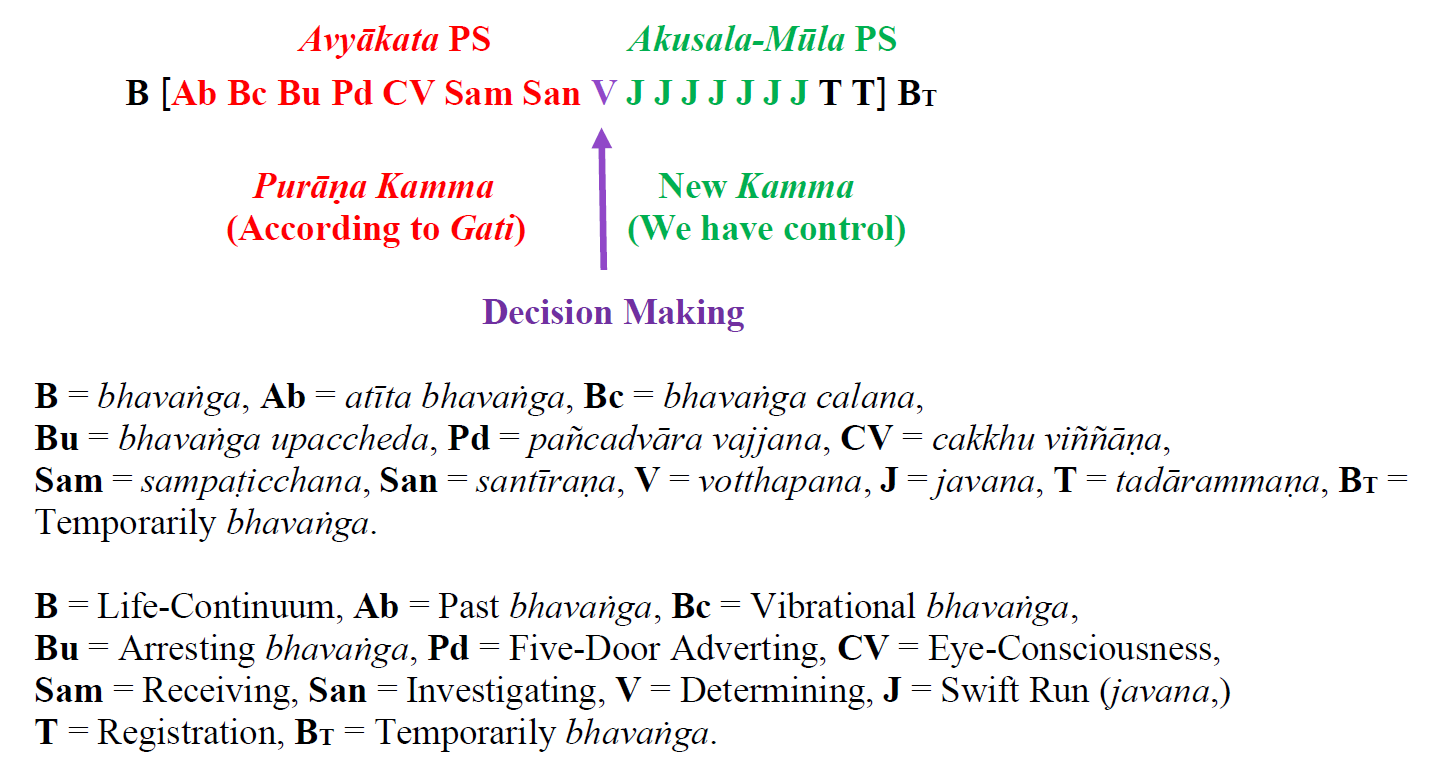

▪The following figure shows a typical thought process (citta vīthi) that starts when the eyes capture a “seeing event” (rūpa ārammaṇa or rūpārammaṇa).

Purāṇa and Nava Kamma

Click the following link to download: “WebLink: Download PDF: Purāṇa and Nava Kamma.”

11. The 17 terms within the square brackets represent the 17 individual cittās in a citta vīthi for a “seeing event.” Note that this process occurs within the blink of an eye; only a Buddha can see such a fast process. Our minds become aware of the sensory input only after hundreds of such citta vīthi run through our minds.

▪A detailed description of a citta vīthi is in “Citta Vīthi – Processing of Sensory Inputs.”

After at least several citta vīthi run through our minds, we become aware of it. Even after that, we can consciously control only the “new (nava) kamma formation” after the votthapana (V) stage; that is possible if we stay mindful. However, unknown to us, the mind had already started “kamma accumulation” even before the votthapana (V) stage, which is the “purāṇa kamma” stage. However, those kammic energies are low because strong vacī or kāya saṅkhāra are generated only in the “nava kamma” stage with javana citta. Let us look at each term in the “purāṇa kamma” stage.

▪As mentioned in #9 above, the mind was in the “neutral uppatti bhavaṅga state” (not a citta, denoted by B in the above figure) before the sensory input. When a sensory input comes in, the mind needs to “break away” from the “neutral uppatti bhavaṅga state,” which takes three cittās: AB, BC, and BU. Then, with the PD citta, the mind looks for the specific sense door where the sensory input is. In the above example, the mind sees that the signal is coming through the “eye door” (or CV) and receives that signal there as a “cakkhu viññāṇa.”

▪That CV citta has an “uncontaminated (but still distorted version) of the external rūpa.” That cakkhu viññāṇa is not defiled but is distorted because it corresponds to a “distorted saññā.” Distorted saññā and viññāṇa arise according to the “uppatti bhavaṅga.” That is why even an Arahant will see “an attractive person” as such, just like an average human does. If the sense input was a taste (say, sugar), the Arahant will taste the sweetness. This is what we call the “dhātu stage.” The next step of “upaya” or “upadhi” also occurs ONLY for a puthujjana within this CV citta. (See “Upaya and Upādāna – Two Stages of Attachment.”) The mind of a puthujjana could automatically attach to that “attractive person” or the “sweetness of sugar,” but the mind of an Arahant will not attach to any ārammaṇa. Thus, the mind of an Arahant will not go through the rest of the citta vīthi as described below. Of course, the citta vīthi will run, but the “javana citta” will be replaced by “kiriya citta” with no kammic effect. From this point, we restrict our attention to the mind of a puthujjana.

▪In the next citta (Sam), the mind may attach to the “rūpa created by the mind with the distorted saññā/viññāṇa.” Here, “sampaṭiccana” (“saŋ” + “paṭicca”) means “attaching with “saŋ.” Thus, this citta generates “saṅkappa” and is not only distorted but is defiled! This rūpa is a “cakkhuviññeyyā rūpā” meaning it was “created (in mind) with a defiled cakkhu viññāṇa.” An Arahant’s mind does not create this rūpa. This is also the “samphassa” stage. [cakkhuviññeyya:[adj.] to be apperceived by the sense of sight.]

▪That “samphassa” then leads to “samphassa-jā-vedanā” in the next citta (San.) We have discussed these two steps in many posts; see, for example, “Vipāka Vedanā and “Samphassa jā Vedanā” in a Sensory Event.”

Based on that “mind-made vedanā,” the mind may attach to that ārammaṇa in the next votthapana citta (V.) This starts the “nava kamma” stage, where strong kammic energies are generated with the seven javana cittās. This is also where “samphassa-jā-vedanā paccayā taṇhā” and “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” steps in Paṭicca Samuppāda occur. (See “Upaya and Upādāna – Two Stages of Attachment.”)

▪Then, in the subsequent seven javana cittās (J), strong “new or nava kamma” accumulation occurs with mano, vacī, and kāya saṅkhāra. Now, the mind starts generating strong kamma CONSCIOUSLY with “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” in the traditional Paṭicca Samuppāda process. See “Paṭicca Samuppāda – Not ‘Self’ or ‘No-Self’”

▪There is an earlier version of what I discussed above in the post “Avyākata Paṭicca Samuppāda for Vipāka Viññāṇa.”

12. It is easier to discuss the difference between “upaya” and “upādāna” with a citta vīthi in Abhidhamma as in the above discussion in #10 and #11. The critical connection to “gati” is quite evident here. To emphasize, the “uppatti bhavaṅga” that one is born with remains until the end of the “human bhava” for anyone born human, including an Arahant. Thus, a “thought process” or a “citta vīthi” arising with a new ārammaṇa (sensory input) starts with that “uppatti bhavaṅga mindset” for all of them. In other words, it begins with the “distorted saññā” inherent in the “kāma loka.” However, it starts only at the initial stage of “kāma dhātu” with ONLY the “distorted saññā.” Within the very first CV citta, it turns into a “defiled saññā” (and thus, a “defiled viññāṇa”) for a puthujjana, but NOT for an Arahant (or an Anāgāmi, whose mind has transcended the “kāma loka.”)

▪Another way to state that is as follows: A puthujjana’s mind ALWAYS sees and perceives the world with “defiled saññā,” i.e., with “sañjānāti.” An Arahant’s mind, in contrast, has realized that “distorted saññā” (of the beauty of an object/person, sweetness of sugar, foul smell of rotten meat, etc.) IS AN ILLUSION. Thus, Arahant’s mind sees the world with perfect wisdom (abhijānāti.) When one becomes a Sotāpanna Anugāmi, one starts to see the “anicca nature” by removing diṭṭhi vipallāsa, the middle stage of “pajānāti.” See “Cognition Modes – Sañjānāti, Vijānāti, Pajānāti, Abhijānāti.”

▪The transition from pajānāti to abhijānāti cannot happen without understanding “saññā vipallāsa,” which occurs at the “upaya” or “upadhi” stage discussed above.

▪The Sutta Piṭaka also discusses the “upaya” step in several suttās, but the above description is the clearest. We will discuss those suttās in upcoming posts.

13. It is unnecessary to understand “saññā vipallāsa” to become a Sotāpanna Anugāmi. However, in my opinion, understanding “saññā vipallāsa” makes it easier for a puthujjana to get a deeper understanding and help get to the Sotāpanna Anugāmi stage.

▪The Buddha compared this “distorted saññā” to a mirage or an illusion in the “WebLink: suttacentral: Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta (SN 22.95).” We discussed that in the previous post, “Sotāpanna Stage and Distorted Saññā.”

▪An Arahant’s mind is “not fooled” by that “distorted saññā.”

▪Just like a thirsty animal chases a mirage (thinking there is a pool of water ahead), a puthujjana chases objects that he perceives to have beauty, taste, etc. He does not realize that beauty or taste is not an intrinsic property of an object.

▪It is critically important to comprehend that our perceptions about “beautiful things/persons, music, delicious foods, sex, etc. ) are mind-made according to gati acquired at birth. They lead to “samphassa-jā-vedanā” arising from saññā vipallāsa.

▪If you re-read the post “Sotāpanna Stage and Distorted Saññā,” you may get a better idea now with the above discussion. As I explained, “Animals generate distinctively different saññā compared to humans and even among different animals. Even though we are repulsed by the sight/smell of rotten meat or feces, a pig gets a very different saññā upon seeing/smelling the same. Thus, while a human would generate repulsive thoughts, a pig will become joyful and be attracted to such things.”

Connection Between Gati and Birth

14. Animals and humans are made of the same atoms and molecules (or the same suddhaṭṭhaka per Buddha Dhamma.) Materially, there is no fundamental reason why pigs like to eat rotten things; cows like to eat grass, lions like to kill other animals and eat their meat, etc. The reason is the specific type of kammic energy responsible for their existence/birth.

▪Each animal’s birth has its origins in a prior human life. A human routinely engaged in “mindless actions” harmful to others will likely be reborn a cow. Those who engage in violent actions are likely to reborn vicious animals like lions, tigers, etc. Most Sinhala words for animals have such “built-in” explanations.

▪Therefore, the only reason why pigs like the smell of rotten meat/feces (and crave them, too) is because, as humans, they cultivated “lowly gati” suitable for pigs. Each pig was a human who cultivated such “distasteful gati” (by engaging in despicable deeds.)

▪It works the other way too. Those humans who engage in meritorious deeds (like giving) and live moral lives are likely to be reborn in the human realm or a Deva realm. Those who cultivate anariya jhāna or samāpatti will be reborn in a Brahma realm. See “Gati to Bhava to Jāti – Ours to Control” and “Gati (Habits/Character) Determine Births – Saṁsappanīya Sutta.”

The “Root of All Things” – Mūlapariyāya Sutta

15. Mūlapariyāya Sutta points out that this “saññā vipallāsa” or “distorted saññā” is responsible for generating craving (taṇhā) for worldly things. Nothing in this world has an intrinsically beautiful/ugly or tasty/distasteful nature.

▪Based on that “saññā vipallāsa” (or sañjānāti), people come up with various wrong views about this world. Those are diṭṭhi vipallāsa. It is possible to remove diṭṭhi vipallāsa from a mind without first removing “saññā vipallāsa.” However, both can be removed by eliminating “saññā vipallāsa.“

▪That is clear from the beginning of the “WebLink: suttacentral: Mūlapariyāya Sutta (MN 1)” with the following verse: “Take an unlearned ordinary person who has not heard about the true nature from a Noble Person and has not grasped the teachings of the Buddha – They perceive pathavi as solid (like in a solid substance,e.g., diamond).” We discussed this specific aspect of “saññā vipallāsa” in the post “Saññā Vipallāsa – Distorted Perception.” Our perception that we have “solid physical bodies” or that “diamond is extremely dense” is an illusion. Both are made of suddhaṭṭhaka (which, in turn, are made by the mind!) and are mostly empty of any substance. For a deeper analysis, see “The Origin of Matter – Suddhaṭṭhaka.”

▪That “saññā vipallāsa” leads to wrong conclusions (@ marker 3.3): “Having perceived earth as solid, they conceive things made of pathavi to be “suitable for me and take pleasure in such things and praise such things.” (“pathaviṁ pathavito saññatvā pathaviṁ maññati, pathaviyā maññati, pathavito maññati, pathaviṁ meti maññati, pathaviṁ abhinandati.) I will write a post later explaining it by clarifying “maññati.”

▪Then the sutta says the same about the other three: āpo, tejo, vāyo.

16. Then the sutta points out that living beings in any of the 31 realms are also “mind-made” because they have origins in Paṭicca Samuppāda, which, in turn, operates based on “saññā vipallāsa,” as I pointed out above, i.e., the main reason for taṇhā to arise at the votthapana (V) stage in #10 above is saññā vipallāsa. Of course, it takes deep contemplation (and re-reading with a calm mind) for these ideas to sink in. As I keep repeating, putting these ideas into words is difficult. One must take the time to read, contemplate, and ask questions.

▪At marker 7.1, the sutta states, “They (puthujjana) perceive creatures as real living beings with intrinsic identity” (“Bhūte bhūtato sañjānāti.”)

▪The Buddha called any living a “bhūta” or a “ghost” because it has that specific identity only for a particular duration (i.e., until the kammic energy that gave rise to it is exhausted). Then, it will take another form. For example, a Deva may be reborn a human or an animal at the end of life. There is no “ever-living Deva, human, or an animal.” They all have transient existences. However, many people worship various Devās, assuming they have some unique existence, yet Devās are also helpless in the rebirth process. They also do not have control over where they will be reborn!

▪The sutta then goes through beings in various realms up to the highest Brahma realm of Nevasaññānāsaññāyatana at marker 18.1. They are all “bhūta existences.” See the connection to yathābhūta ñāṇa (or “knowledge about the true nature of things”) in the post “Bhūta and Yathābhūta – What Do They Really Mean.” Also, see the links in #14 above.

17. At marker 19.1, it states, “They (puthujjana) perceive the seen as something real. (“Diṭṭhaṁ diṭṭhato sañjānāti.”)

▪This is what we specifically discussed in #10 – #12 above. A puthujjana “incorrectly perceives” (sañjānāti)” some object or a person to be attractive (or ugly.) But there is nothing intrinsically attractive or ugly in a form (rūpa) in the external world. They are made of the SAME pathavi, āpo, tejo, vāyo.

▪However, the mind, based on the “distorted/defiled perception or sañjānāti” makes its own “cakkhuviññeyyā rūpā” or “a misleading version of the external rūpa created by the defiled mind.” In most suttās, “rūpa” refers to this “mind-made version” instead of the external rūpa. Thus, what the mind generates as a “beautiful person” is only a physical body made of pathavi, āpo, tejo, vāyo. A lion looking at the same person may be thinking about not its beauty but the suitability for a meal! Even among humans, different people could conceive the same person as either beautiful or not so beautiful.

▪Then, that verse repeated for what is heard, smelled, etc. All those are “mind-made impressions” based on sañjānāti.

18. A new section of the sutta starts at marker 27.1, repeating the above-discussed verses for a sekha (“a trainee” or a Noble Person striving to be an Arahant”): “A bhikkhu who is a trainee, who hasn’t achieved Arahanthood but lives aspiring to be one, knows the true nature of pathavi and things made of pathavi (abhijānāti.)

▪They have comprehended (abhijānāti) how anything in this world originates in the mind based on saññā vipallāsa.

▪Therefore, @ marker 27.4, “they try to abstain from both taking pleasure or praising such things.” (“pathaviṁ pathavito abhiññāya pathaviṁ mā maññi, pathaviyā mā maññi, pathavito mā maññi, pathaviṁ meti mā maññi, pathaviṁ mābhinandi.”) Here, “mābhinandi” is “mā abhinandi” or “strive to abstain from praising.”

▪The rest of the verses proceed along the same lines, explaining that a sekha will strive to fully comprehend that the life of any living being arises based on saññā vipallāsa.

19. When that comprehension is complete, one has attained the Arahanthood, as explained starting at marker 75.1. An Arahant has fully comprehended (abhijānāti) how anything in this world originates in the mind based on saññā vipallāsa.

▪Therefore, @ marker 75.2, “they do not take pleasure in or praise such things.” (“pathaviṁ pathavito abhiññāya pathaviṁ na maññi, pathaviyā na maññi, pathavito na maññi, pathaviṁ meti na maññi, pathaviṁ nābhinandi.”) Here, “nābhinandi” is “na abhinandi” or “never take pleasure in or praise such things.”

▪Then, @ marker 75.4, it says the reason is that an Arahant has no greed left in mind (“Khayā rāgassa, vītarāgattā.”)

▪That sequence is repeated twice, saying that Arahants are also free of hate (@ marker 99.4) and delusion/moha (@ marker 123.4.)

20. Finally, @ marker 147.1, the sequence of #19 above is repeated for a Buddha (Sammāsambuddha.)

Summary

21. I have tried to present the key ideas/concepts embedded in the Mūlapariyāya Sutta. As for any critical sutta, it will take a book to describe the ideas/concepts fully.

▪However, if someone can take the time to read the background material recommended in #1 of the first post in this subsection, “Sotāpanna Stage and Distorted Saññā” and also read all the recommended links above, it should be possible to understand the key concepts.

▪Of course, this post (or any other post) can be improved. Please don’t hesitate to point out any mistakes or ask for clarification on anything unclear.

▪It is an unusually long post, but I wanted to convey most of the main ideas in one post. Based on critical comments, we can improve it.