October 23, 2018; revised May 4, 2020; November 14, 2020; March 11, 2021; May 27, 2021; April 12, 2022; major revision July 28, 2022; rewritten with chart March 3, 2023; revised August 26, 2024

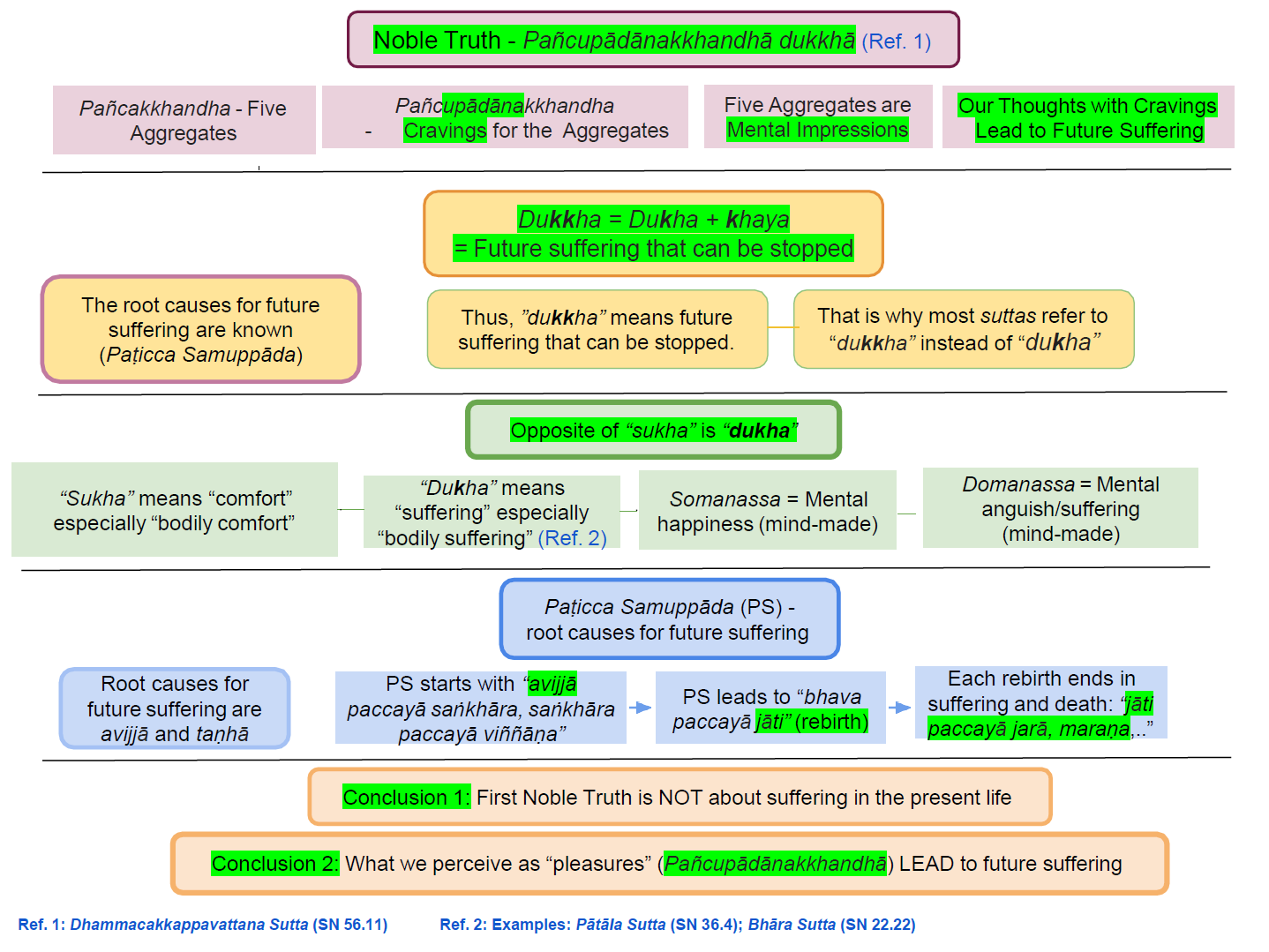

The essence of Buddhism (Buddha Dhamma) is in the first sutta delivered by the Buddha, Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta. We discuss the verse “saṅkhittena pañcupādānakkhandhā dukkhā” in detail. [saṅkhittena means through overthrown by defilements, khitta : [pp. of khipati] thrown; overthrown; casted away; upset.]

Suffering That Can Be Eliminated

Download/Print: “WebLink: PDF Download: 4. Dukkha – Future Suffering”

1. This sutta states the Four Noble Truths in summary form. It takes a determined effort to understand them. This post will focus on the verse stating the First Noble Truth.

▪In particular, we highlight that this verse is about “suffering” that can be stopped from arising.

▪The Pāli word for “suffering” is “dukha” (with one k.) The word dukkha (with two k’s) means “suffering that can be eliminated” (dukha + khaya.)

▪Not many suttās use the word “dukha” because the ability to escape that suffering is always emphasized with “dukkha.” In the “WebLink: suttacentral: Pātāla Sutta (SN 36.4),” dukha is used to describe the painful feelings present in the apāyās (pātāla or the “abyss.”) More examples in “Does the First Noble Truth Describe only Suffering?“

First Noble Truth in Just a Single Verse!

2. Let us examine how the Buddha summarized the First Noble Truth about suffering in the “WebLink: suttacentral: Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56.11).”

“Idam kho pana, bhikkhave, dukkhaṁ ariya saccam:

jātipi dukkhā, jarāpi dukkhā, byādhipi dukkho, maraṇampi dukkhāṁ, appiyehi sampayogo dukkho, piyehi vippayogo dukkho, yampicchaṁ na labhati tampi dukkhāṁ—saṅkhittena pañcupādānakkhandhā dukkhā.”

Translated: Bhikkhus, What is the Noble Truth of Suffering?

“Birth is suffering, getting old is suffering, getting sick is suffering, dying is suffering. Having to associate with things one dislikes is suffering and separation from those one likes. If one does not get what one likes/craves/desires, that is suffering – in brief, the origin of suffering is the craving for the five aggregates of rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, viññāṇa (pañcupādānakkhandha). Pancupādānakkhandha (upādāna or craving/desire for pañcupādānakkhandha) represents all we crave in this world.”

▪The fact that pañcupādānakkhandha represents one’s world is discussed in “The Five Aggregates (Pañcakkhandha).” But read this post first.

▪(Here, I have translated upādāna as craving. However, the word upādāna cannot be represented by just one word. It is a good idea to grasp the meaning. See “Concepts of Upādāna and Upādānakkhandha.”)

▪There are four sections in that verse. I have highlighted alternating parts to explain each of the four below.

The Key Aspects of Suffering

3. The first part in bold indicates what we consider forms of suffering: Birth, getting old, getting sick, and dying.

▪Every birth ends up in death. That is why rebirth is suffering. All births — without exception — end up in death.

▪We also DO NOT LIKE to get old, get sick, and do not like to die. If we experience any of those, that is suffering.

▪We WOULD LIKE it to stay young, not get old, not get sick, and not die ever. If we can have those conditions fulfilled, we will be forever happy.

▪Therefore, it is clear that the Buddha focused on the suffering associated with the rebirth process in his first discourse.

Root Cause of Suffering – Not Getting What One Desires

4. Anyone can see that not getting what one desires/craves is suffering.

▪The second part of the verse in #2 (in black) says: Having to associate with things that one does not like is suffering, and having to separate from those one wants is suffering. That must be evident to all.

▪That is stated in one concise statement in the third part of the verse in #2 (in red): “yampicchaṁ na labhati tampi dukkhaṁ.”

Yampicchaṁ na labhati tampi dukkhaṁ

5. “Yampicchaṁ na labhati tampi dukkhaṁ” is a shortened version of the verse (that rhymes). The complete sentence is “Yam pi icchaṁ na labhati tam pi dukkhaṁ.”

▪“Yam pi icchaṁ” means “whatever is liked or craved for.” “Na labhati” means “not getting.” “tam pi dukkhaṁ” means “that leads to suffering.”

▪Therefore, that verse says: “If one does not get what one likes/craves/desires, that leads to suffering.”

▪That is a more general statement and applies to any situation. We can see that in our daily lives. We wish to hang out with people we like, and being with people we do not like is stressful.

▪Furthermore, the more one craves something, the more suffering one will endure. But this requires a lot of discussion.

▪Note that “iccha” (and “icca”) is pronounced “ichcha.” See ““Tipiṭaka English” Convention Adopted by Early European Scholars – Part 1” and Part 2 there.

6. Thus, the “Yampiccam nalabhati tampi dukkhaṁ” (“Yam pi icchaṁ na labhati tam pi dukkhaṁ”) verse gets us closer to the deeper meaning of the First Noble Truth on suffering.

▪Note that icca and iccha (ඉච්ච and ඉච්ඡ in Sinhala) are used interchangeably in the Tipiṭaka. The word “iccha” with the emphasis on the last syllable (with “h”) indicates “strong icca” or “strong attachment.”

▪The word “icca” (liking) is closely related to “taṇhā” (getting attached). Tanhā happens automatically because of icca.

▪Not getting what one desires or craves is the opposite of “icca” or “na icca” or “anicca.” That is the same way that “na āgami” becomes “Anāgāmi” (“na āgami” means “not coming back”; but in the context of Anāgāmi, it means “not coming back to kāma loka or the lowest 11 realms. Both these are examples of Pāli sandhi rules (connecting two words).

Connection to the Anicca Nature

7. Therefore, even though we like/desire (icca/iccha) some things in this world, those expectations are not met in the long run. In particular, we have to give up everything at least at death.

▪That is why the intrinsic nature of this world is “anicca.” When we don’t get what we desire, we suffer. That suffering is UNAVOIDABLE in two situations: (i) at death, we will have to leave all we crave, and (ii) even though we don’t like to be reborn in “suffering-filled realms,” that is where most rebirths take place. That is why the world is of an “anicca nature” and leads to dukkha.

▪However, we wrongly believe that the world is of a “nicca nature,” i.e., our desires/expectations can be attained AND maintained. Thus, another (and related) way to explain anicca as the opposite of “nicca”; see “Three Marks of Existence – English Discourses.”

“Saṅkhittena Pañcupādānakkhandhā Dukkhā”

8. The last part of the verse in #2, “saṅkhittena pañcupādānakkhandhā dukkhā,” will take much more explaining. One first needs to understand pañcakkhandhā (the five aggregates of rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, viññāṇa) even to begin to understand this part.

▪Here, pañcupādānakkhandhā is entirely mental and defines one’s world.

▪Pañcupādānakkhandhā (pañca upādāna khandhā) includes all that we crave in the world! We accumulate bad kamma (via abhisaṅkhāra) to fulfill our cravings and do not realize that it is why we are trapped in this suffering-filled rebirth process!

▪Most people have no idea what pañcakkhandhā and pañcupādānakkhandhā mean.

▪These concepts are discussed in detail in “The Five Aggregates (Pañcakkhandha).” We will discuss this in detail again in this series: “Buddhism – In Charts.”

9. Each person’s world is what one experiences, i.e., the five aggregates of clinging/pañcupādānakkhandhā of rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, viññāṇa.

▪Some of our experiences (i.e., pañcupādānakkhandhā) are mind-pleasing, and we attach to them further after the upādāna stage. Such stronger attachments lead to strong kamma generation (via vacī and kāya kamma), leading to rebirth and more suffering. See “Purāṇa and Nava Kamma – Sequence of Kamma Generation.” Thus, future suffering cannot be stopped until we understand the details of this process (Paṭicca samuppāda). That understanding (the Buddha himself reached upon Buddhahood) leads to the end of the rebirth process and the end of future suffering.

▪After explaining the four Noble Truths (we briefly discussed just the First Noble Truth), the Buddha says in the middle of the sutta: “Ñāṇañca pana me dassanaṁ udapādi: ‘akuppā me vimutti, ayamantimā jāti, natthi dāni punabbhavo'” ti.”

Translated: “The knowledge and vision arose in me: ‘unshakable is the liberation of my mind. This is my last birth. There is no more renewed existence.'”

Misconceptions on Dukkha Sacca, Pañcakkhandhā, and Pañcupādānakkhandhā

10. Many think that Dukkha Sacca (the First Noble Truth, pronounced “dukkha sachcha”) says everything is suffering. That is not true; there are a lot of “pleasures” to enjoy in this world.

▪The first three parts of the verse in #2 that summarizes the First Noble Truth explain that there is “hidden suffering” in the world that an average person would not see. Even though people celebrate birthdays, we get closer to death with each birthday passing. Even though we desire to be with those we love forever, separation from them is inevitable, at least at death.

▪The last part of the verse is the critical part of the First Noble Truth. It is not a type of suffering but the root cause of (future) suffering. We become subjected to suffering because we attach to certain rūpa in this world and also to vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, and viññāṇa that arise from interactions with such rūpa. That is pañcupādānakkhandhā (pañca upādāna khandhā), loosely meaning “attachment to the pañcupādānakkhandhā.”

▪Also, see “Does the First Noble Truth Describe only Suffering?” and “First Noble Truth is Suffering? Myths about Suffering.”

We Don’t See the “Hidden Suffering” in Sensory Pleasures

11. That is until a Buddha explains it! The Buddha gave the following analogy to describe the “hidden suffering” humans don’t see.

▪When a fish bites bait, it does not see the suffering hidden in that action. Looking from the ground, we can see the whole picture and know what will happen to the fish if it bites the bait. But the fish cannot see that whole picture and thus does not see the hidden suffering (the hook hidden in the bait.) It can only see the bait (a delicious bit of food.)

▪In the same way, if we do not know about the wider world of 31 realms (with the suffering-laden four lowest realms) and that we have gone through unimaginable suffering in those realms in the past, we only focus on what is easily accessible to our six senses.

▪That analogy is in the “WebLink: suttacentral: Baḷisa Sutta (SN 17.2).”

▪Further details in “Is Suffering the Same as the First Noble Truth on Suffering?” and “Does the First Noble Truth Describe only Suffering?“

▪The mindless translation of “dukkha” as “suffering.” everywhere (without understanding that the primary reference is to the “suffering in the rebirth process”) has led to confusion, such as whether an Arahant is free of “all suffering” even while living. Another confusion is what is meant by “Nibbāna.” It simply means “the end of the rebirth process.” All suffering ends with the death of Arahant.

A Sutta Is a Highly Condensed Summary

12. Some people think the Buddha recited each sutta as it appears in the Tipiṭaka. That could be why suttā are translated word-by-word by most translators today. But that is far from the truth.

▪As we saw above, Dhammacakkappavattana sutta is highly condensed (as many suttā are). Even a single verse takes a lot of explaining. Further analysis of the sutta in this subsection: “Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta.”

▪The Buddha delivered Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta to the five ascetics over several days. See “The Life of the Buddha” by Bhikkhu Nānamoli.” A direct account from the Tipiṭaka at “WebLink: The Long Chapter (Mahākhandhaka) (Vinaya Kd 1);” see “Section 6. The account of the group of five.”

▪Only Ven. Kondañña attained the Sotāpanna stage on the first night. Then the Buddha explained the material over several days. The other four ascetics reached the Sotāpanna stage over several days.

▪The above book contains many passages from the Vinaya Piṭaka of the Tipiṭaka, which provide many details unavailable in the suttā. It also provides the timeline of critical suttā and significant events.

13. Therefore, the Buddha did not recite each sutta as it appears in the Tipiṭaka. If so, it would have been delivered within 15 minutes! Instead, the discussion of the sutta continued for several days until all five ascetics attained the Sotāpanna stage. Attaining magga phala is not a magical process. In particular, the Sotāpanna stage requires only understanding the worldview of the Buddha.

▪It will take many people a lifetime to fully understand the Dhammacakkappavattana sutta.

▪We must remember that many generations transmitted all the suttā in the Tipiṭaka orally. Tipiṭaka was written down about 500 years after the Parinibbāna of the Buddha. See “Preservation of the Dhamma.”

▪It appears that the Buddha summarized the material in each sutta concisely to a limited number of verses suitable for oral transmission (easy to remember); see “Sutta Interpretation – Uddesa, Niddesa, Paṭiniddesa.”

▪Summarized verses must be explained in detail by those who have understood them. As we have seen, even single words like “anicca” and “dukkha” need detailed explanations (not merely “impermanence” and “suffering.”) Those words DO NOT have corresponding single words in other languages. We must use those Pāli words with an understanding of their meanings.