December 21, 2019; re-written October 14, 2022 (#4 revised later)

Upādāna Is a Key Concept That Has Been Hidden

1. The Buddha declared that his Dhamma or teachings on suffering “had not been known to the world” before him. In his first discourse, WebLink: suttacentral: Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56.11), he “defined” dukkha or suffering.

Idaṁ kho pana, bhikkhave, dukkhaṁ ariyasaccaṁ:

jātipi dukkhā, jarāpi dukkhā, byādhipi dukkho, maraṇampi dukkhāṁ, appiyehi sampayogo dukkho, piyehi vippayogo dukkho, yampicchaṁ (yam pi icchaṁ) na labhati tampi dukkhāṁ—saṁkhittena pañcupādānakkhandhā (pañca upādāna khandhā) dukkhā. [saṅkhittena means through overthrown by defilements]

Translated: Bhikkhus, What is the Noble Truth of Suffering?

“Birth is suffering; getting old is suffering; getting sick is suffering; death is suffering. Having to associate with things one does not like is suffering and having to separate from those one likes is suffering. If one does not get what one wants/craves (icchā), that is suffering – in brief, the origin of suffering is the “pulling close” (upādāna) of the five aggregates of rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, viññāṇa (pañcupādānakkhandha). [iccha :[adj.] (in cpds.), wishing; longing; desirous of.]

▪Everyone knows that “Birth is suffering, getting old is suffering, getting sick is suffering, dying is suffering. Having to associate with things that one does not like is suffering. Having to separate from those things one likes is suffering.” That part is known to the world.

▪It may be a bit harder to understand birth as suffering, but ANY birth ends with decay and death at the end, so it is not that difficult to “see.”

The “Hard-To See” Suffering That Is Hidden

2. What is “previously unheard” is that craving (icchā) for sensory attractions leads to suffering in the future. When one craves something, one will start thinking and speaking (vacī saṅkhāra), and doing things (with kāya saṅkhāra) to “get possession” of it. That “pulling close” of “mind-pleasing things” is “upādāna” (“upa” + “ādāna” as we discussed before.) [Upādāna means “pulling it closer (in one’s mind)” (“upa” + “ādāna,” where “upa” means “close” and “ādāna” means “pull”). [ādāna : (nt.), taking up; grasping.]]

▪Since we do not “see” that hidden suffering, we tend to do immoral deeds to possess such “mind-pleasing things.” That means generating (mano, vacī, and kāya) saṅkhāra due to our avijjā (ignorance of the core teachings of the Buddha, including the Paṭicca Samuppāda process.)

▪The harsh consequences of such immoral deeds (kamma vipāka) may not be seen immediately, or even in this life. That is why it is hard to “see” this hidden suffering.

▪That is contrary to our daily experiences. We do everything to live a luxurious life with a beautiful house, an attractive spouse, a nice car, etc. We do not see “any bad consequences” of our efforts to pursue those “mind-pleasing things.”

A Fish Does Not “See” the Hidden Suffering in a Delicious Bait

3. As we will discuss, we are no different than a fish biting into a tasty bait, say, a worm. That fish does not see the hook hidden in the “delicious worm.” It will be subjected to much suffering once it bites the worm, and the hook attaches to its mouth.

▪The difficulty in our case is that our deeds to get those sensory pleasures may not show their CONSEQUENCES in this life. It is useless to follow Buddha Dhamma if one does not believe in rebirth or kamma/vipāka.

▪All we tend to crave (icchā) are PARTS OF the five aggregates (pañcakkhandha). That small part is pañcupādānakkhandha. We like certain types of rūpa (people and things), certain types of vedanā (feelings), etc.

▪That is why it is critical to understand how “pulling close” (upādāna) of sensory inputs (ārammaṇa) leads to future suffering. The Akusala-Mūla Paṭicca Samuppāda (PS) ends up in “jarā, maraṇa, soka, parideva, dukkha, domanassa,..” or the “whole mass of suffering.”

Craving (Icchā) Starts the Paṭicca Samuppāda Process That Leads to Suffering

4. In the previous two posts, we discussed how an external sensory input (ārammaṇa) triggers the “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” step in the PS. See, “Taṇhā Paccayā Upādāna – Critical Step in Paṭicca Samuppāda” and “Moha/Avijjā and Vipāka Viññāṇa/Kamma Viññāṇa.”

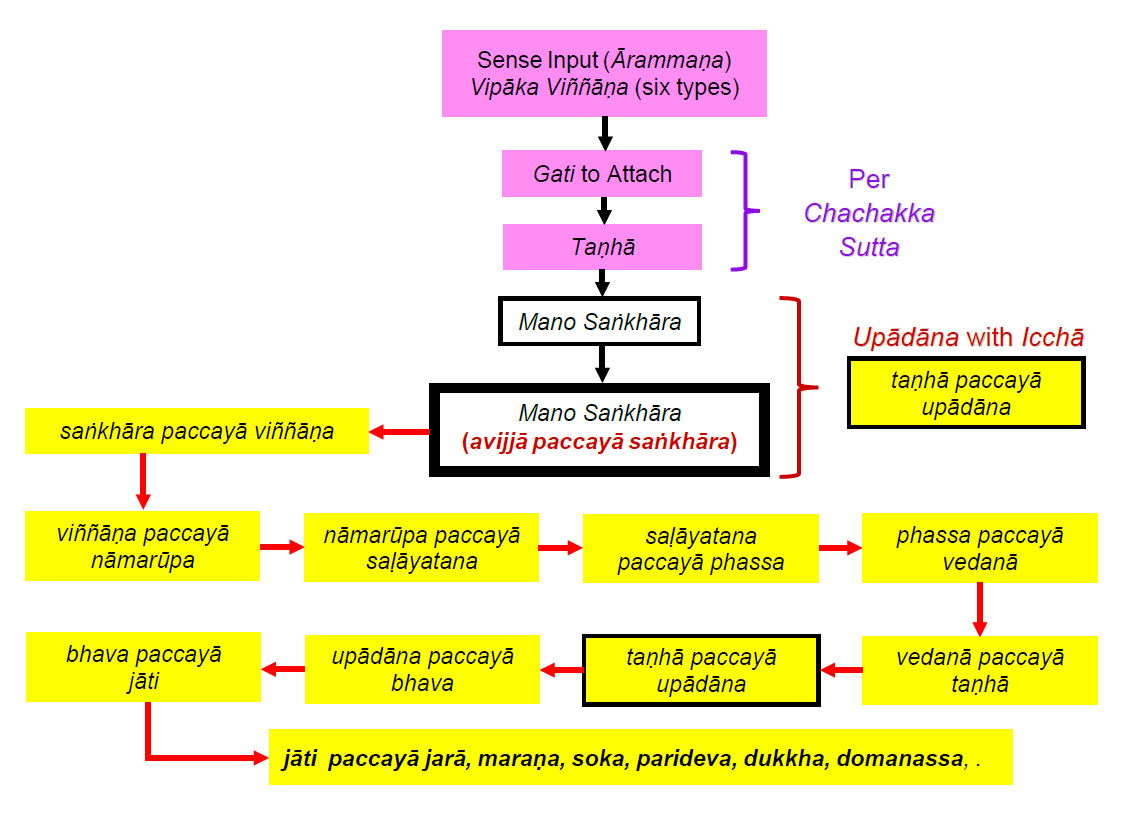

▪Continuing that discussion, let us look at how that future suffering arises. The following chart summarizes what we discussed. It shows all the steps in the PS process, starting with “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” to the end, “jarā, maraṇa, soka, parideva, dukkha, domanassa,..” or the “whole mass of suffering.”

▪However, the initiation of PS cycles is not at the “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” step but the “(sam)phassa paccayā vedanā” step. Attaching to a sensory input (ārammana) with liking (icchā) happens first. See #3 of “Chachakka Sutta – Six Types of Vipāka Viññāna.”

Open pdf for viewing or printing: “WebLink: PDF-file: Icchā to Upādāna to Suffering.”

Idappaccayatā Paṭicca Samuppāda Example

5. Idappaccayatā Paṭicca Samuppāda explains phenomena occurring in real-time as they happen. That is easier to interpret compared to upapatti Paṭicca Samuppāda, which describes events leading to future lives, especially in rebirths. [idaṁ :[(Nom.and Acc.sing.of ima) nt.] this thing. paccayatā :[f.] causation. idappaccayatā : (idaṁ + paccayatā) [f.] having its foundation on this, i.e., causally connected.]

▪Let us revisit a simple example that we discussed in #13 of the recent post, “Vacī Saṅkhāra – Saṅkappa (Conscious Thoughts) and Vācā (Speech).”

A person is in the waiting room to see a doctor and sees that someone has dropped a wallet. The moment he sees the wallet, his mind attaches to it (taṇhā). Then he thinks there could be some money in the wallet and that it is an easy way to get some “free money.” That happens within moments of him seeing the wallet.

▪“Seeing the wallet” is a cakkhu viññāṇa that resulted via, ”Cakkhuñca paṭicca rūpe ca uppajjati cakkhu viññāṇaṁ.” Within a split-second, he attaches to it (taṇhā) as we discussed in the posts on Chachakka Sutta (MN 148.)

▪Then he starts thinking about how much money can be in that wallet, and how to pick it up without being noticed. Those are vacī saṅkhāra that arise due to his ignorance (avijjā) about their harmful consequences. Thus, his mind has generated “upādāna” for the wallet because he has a craving (icchā) for money.

▪Thus, his mind starts the step, “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” in Paṭicca Samuppāda (PS.)

Initiation of a new Paṭicca Samuppāda Process

6. Therefore, the “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” step now leads to the start of a brand new PS process with “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” (see the chart above.) We discussed that in the previous post, “Moha/Avijjā and Vipāka Viññāṇa/Kamma Viññāṇa.“

▪Those conscious thoughts about the wallet are vacī saṅkhāra. Now those saṅkhāra lead to a NEW kamma viññāṇa. That viññāṇa has the expectation of picking up the wallet and keeping it for himself. That is a mano viññāṇa that arises in his mind and is different from the cakkhu viññāṇa of “seeing the wallet.”

▪Now, that kamma viññāṇa leads to “nāmarūpa formation” in his mind. He runs various scenarios in his mind (vitakka/vicāra), both regarding picking up the wallet without being noticed and what he can do with the money in the wallet. That is “viññāṇa paccayā nāmarūpa.”

▪That immediately leads to the involvement of several internal āyatana. For example, he may look around to see whether anyone is watching. He may stand up and see whether the receptionist can see the area where he is sitting, etc. That is “nāmarūpa paccayā salāyatana.”

▪That, in turn, leads to “salāyatana paccayā (sam)phassa.” His mind’s defilements (or “saŋ” or anusaya) affect all his thoughts and activities. That generates mind-made vedanā or “(sam)phassa paccayā (samphassa-jā-)vedanā” followed by more PS cycles. Those are the steps described in the Chachakka Sutta.

▪We need to remember that words like “phassa” and “vedanā” in the abbreviated PS must be interpreted as “samphassa” and “samphassa-jā-vedanā.” See the previous posts in this series: “Worldview of the Buddha.”

Strengthened Upādāna Leads to a Temporary Bhava

7. His mind is now back to the “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” step in the PS process, and it reinforces that upādāna. The above steps may be repeated many times in his mind as he sits there and contemplates various aspects. Those, by the way, are vitakka/vicāra.

▪With the strengthening of the upādāna, now his mindset changes to that of a thief’s existence (bhava). That is “upādāna paccayā bhava.” Then immediately, he is “born” (jāti) a thief. That is “bhava paccayā jāti,” By the way, in upapatti Paṭicca Samuppāda, jāti can happen much later. The “bhava” remains energized as dhammā; see below.

▪Now that “thief” goes and picks up the wallet and puts it in his pocket. Now, “stealing of the wallet” is accomplished. That is the “maraṇa” or “death” of that particular jāti as a thief.

▪However, there is more to it than just maraṇa. “Jarā, maraṇa, soka, parideva, dukkha, domanassa,..” will also follow.

▪Even though he got what he wanted, his mind is very agitated. Even though no one else was in the waiting room, he wondered whether the receptionist somehow saw his act. Also, now a new thought comes to his mind as to whether there is a video camera in the room. That “mental stress” is part of domanassa.

The Process Is Over, but the Consequences Will Prevail

8. It is possible that there was a video camera in the room. If so, he could be charged with theft a few days later. Those are part of the “mass of suffering” due to the immoral act of stealing.

▪But the critical point is the following. Even if he did not get caught, he would be paying for his immoral action in the future. The kammic energy of that immoral deed will follow him, waiting for an opportunity to bring a corresponding “bad vipāka” at some point.

▪Kammic energy is in dhammā (with a long “a” at the end, not as in Buddha Dhamma.) Let us address that in brief.

Dhammā Are Energies Created by Mind – With Kamma Viññāṇa

9. Dhammā are the underlying energies (or “kamma seeds” or “kamma bīja”) created by the mind.

▪A seed has the POTENTIAL to give rise to a tree under proper conditions like good soil, water, and sunlight. In the same way, dhammā (a kamma bīja) has the POTENTIAL to give rise to things (both living and inert) in this word.

▪That is how such dhammā (or kamma seeds) can bring vipāka in the future.

▪Just like an ordinary seed needs soil, water, and sunlight to germinate and bring about a tree, dhammā needs proper conditions to bring about corresponding vipāka. That is also why kamma is not deterministic. For example, Aṅgulimāla killed 999 people. That kammic energy was there even after Ven. Aṅgulimāla attained Arahantship. However, with that Arahantship, his mind became pure, and any conditions to bring about the vipāka of such bad kamma could not materialize. See, “Account of Aṅgulimāla – Many Insights to Buddha Dhamma.”

▪The role of dhammā is discussed in “Dhammā, Kamma, Saṅkhāra, Mind – Critical Connections.”

Icchā (Cravings) Lead to Upādāna and to Eventual Suffering

10. What we discussed above is the key message embedded in the First Noble Truth of Dukkha Sacca (pronounced “sachcha.”)

▪It is craving (icchā) for “mind-pleasing sensory attractions in the world” that lead to taṇhā and upādāna and eventual suffering.

▪Based on icchā, we get “stuck in attractive sensory inputs” (taṇhā), and try to keep that ārammaṇa as close as possible in mind (upādāna.) We do that in our minds by generating unwise thoughts (vacī saṅkhāra), which leads to unwise speech (more vacī saṅkhāra) and immoral actions (based on kāya saṅkhāra). That is the start of an Akusala-Mūla PS process, “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra.”

▪That process, of course, inevitably leads to the last step in the PS process, “jarā, maraṇa, soka, parideva, dukkha, domanassa,..” or the “whole mass of suffering.”

11. The “WebLink: suttacentral: Icchā Sutta (SN 1.69)” summarizes the importance of the icchā. One time, a deva came to the Buddha and asked:

“Kenassu bajjhatī loko, kissa vinayāya muccati; Kissassu vippahānena, sabbaṁ chindati bandhanan”ti. |

“By what is the world bound? By the removal of what one is freed? What is it that one must abandon To cut off all bondage?” |

[bajjhati :[pass. of bandhati] is bound or captivated; is caught.

vinaya :[m.] discipline; the code of monastic discipline; removal.

muccati :[muc + ya] becomes free; to be saved or released.

vippahāna : (nt.) [vi+pahāna] leaving, abandoning, giving up.

chindati :[chid + ṁ + a] cuts; severs; destroys.

bandhana :[nt.] bound; fetter; attachment; imprisonment; binding; bondage; something to bind with.]

The Buddha replied:

“Icchāya bajjhatī loko, icchāvinayāya muccati; Icchāya vippahānena, sabbaṁ chindati bandhanan”ti. |

“By cravings, one is bound to the world; By the removal of desire one is freed Craving is what one must give up To cut off all bondage.” |

▪But, of course, the craving for “mind-pleasing things” cannot be removed by just willpower. One must understand the harmful consequences of such cravings. That understanding comes through moral living AND learning true and correct Buddha Dhamma.

▪That is why Sammā Diṭṭhi comes first in the Noble Eightfold Path. The other steps in the Path will follow once one comprehends the teachings. But a badly corrupt mind cannot grasp those teachings, which is why moral living is a prerequisite.

12. The following posts discuss more examples that may help solidify the understanding: “How Do Sense Faculties Become Internal Āyatana?” and “Key Steps of Kammic Energy Accumulation.”

▪The Idappaccayatā Paṭicca Samuppāda is discussed in detail in “Paṭicca Samuppāda During a Lifetime.”