Re-written April 17, 2020; revised April 19, 2020; October 30, 2022; rewritten with new chart, March 9, 2023

Five Aggregates (pañcakkhandha) is not one’s own body, as many believe. It is one’s whole world (i.e., everything one experiences,) including all experiences from previous lives.

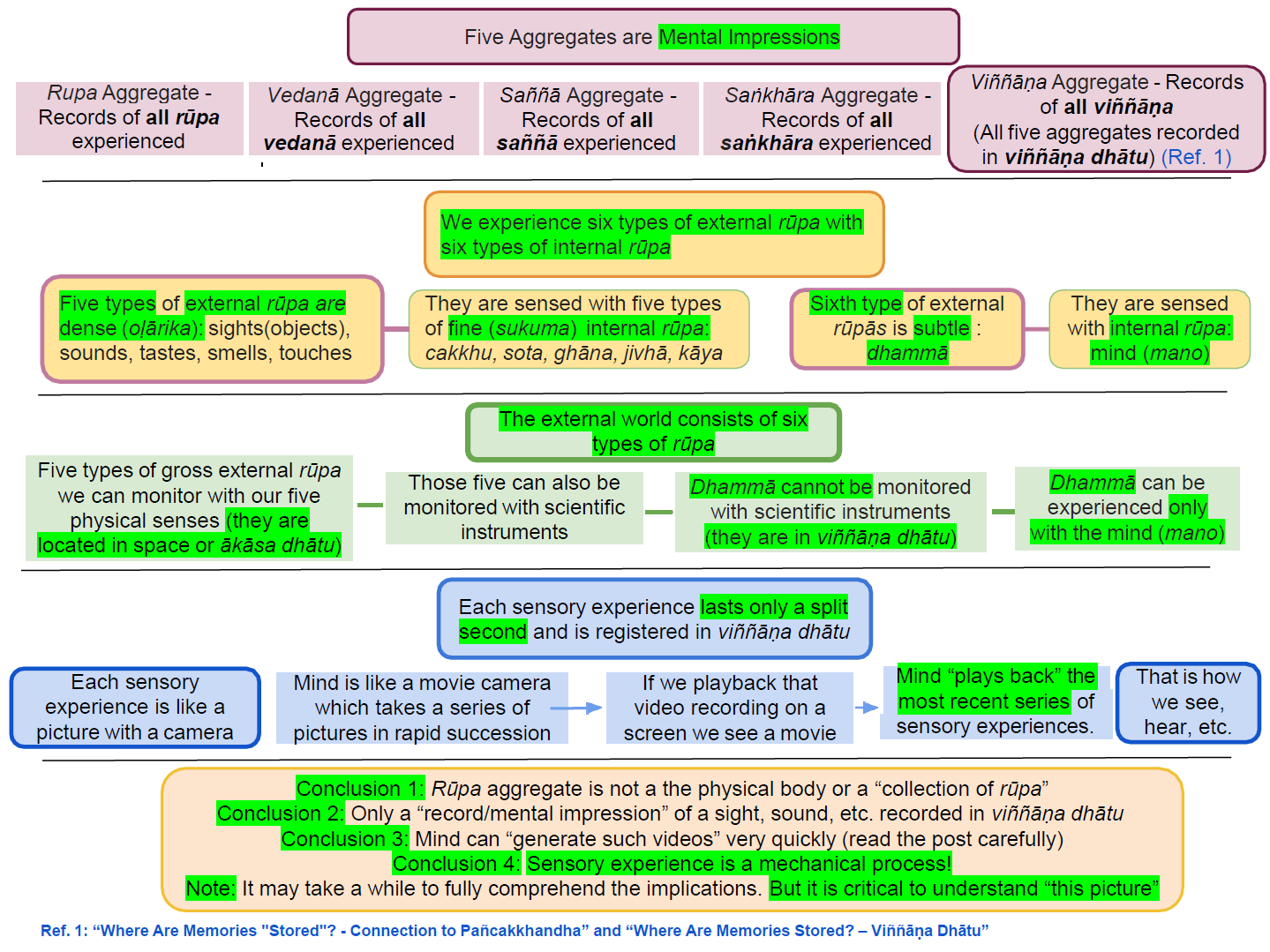

Definition of the Five Aggregates

Download/Print: WebLink: PDF Download: Chart #5. Five Aggregates – Mental Impressions

1. Five aggregates (pañcakkhandha) are unique to each sentient being. We can see that by carefully analyzing a short sutta about the five aggregates: “WebLink: suttacentral: Khandha Sutta (SN 22.48).” (Ref. 1)

“And what are the five aggregates?”

▪“Any kind of rūpa at all—past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near: this is called the aggregate of rūpa.”

▪“Any kind of vedanā at all—past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near: this is called the aggregate of vedanā.”

▪“Any kind of saññā at all—past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near: this is called the aggregate of saññā.”

▪“Any kind of saṅkhāra at all—past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near: this is called the aggregate of saṅkhāra.”

▪“Any kind of viññāṇa at all—past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near: this is called the aggregate of viññāṇa.”

Therefore, each aggregate comprises 11 types: past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near.

Brief Description of the 11 Types of Rūpa

2. A set of rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, and viññāṇa arise whenever the mind makes contact with an external rūpa. Those can be of six types: vaṇṇa rūpa, sadda rūpa, gandha rūpa, rasa rūpa, phoṭṭhabba, and dhamma rūpa (n plain English, sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and dhammā.) Note that “vaṇṇa rūpa” are also called “rūpa rūpa” or simply “rūpa.” Thus, depending on the context, one must be able to see what “rūpa” means. Six types of internal rūpa: They are cakkhu, sota, ghāna, jivhā, kāya, and mana. Note that these six are in the manomaya kaya (gandhabba) first five are pasāda rūpa, and the sixth is hadaya vatthu. They make contact with the six external rūpa. The Buddha called these 12 types of rūpa to be “all” because all experiences in this world arise via them; see “WebLink: suttacentral: Sabba Sutta (SN 35.23).”

▪Rūpa we can see are coarse rūpa. The others (particularly the six internal rūpa and dhammā) belong to the “fine rūpa” category.

▪Any rūpa in the “good realms” are “superior rūpa,” and those in the lower realms are “inferior rūpa.“

▪When one thinks about close-by rūpa, those are “near rūpa.” When one contemplates far away rūpa, they are “far rūpa.”

▪All those eight types of rūpa can belong to past, future, or present categories. “Past rūpa” are those one has experienced in the past; as we can see, this category is infinite since there is no beginning to the rebirth process. The “present rūpa” category is the smallest since it lasts only while a rūpa is experienced. “Future rūpa” is a bit complex category. Our future experiences are automatically “mapped out” according to the present status of the mind. However, it is a dynamic set that keeps changing. Only when a Bodhisatta gets “niyata vivarana” to become a Buddha will his future become fixed. That explanation requires a separate post.

▪The other four aggregates similarly fall into the same 11 categories. For details, see “The Five Aggregates (Pañcakkhandha).”

How Do the Five Aggregates Arise?

3. It is a sensory experience that triggers a “new addition” to the set of five aggregates. For example, “seeing an object” means the contact of an external rūpa with an internal rūpa.

▪That leads to “vedanā” and “saññā” arising in mind automatically (to recognize the object and there is a vedanā associated with it). Then the mind generates “saṅkhāra” according to one’s gati. That sensory experience is a “vipāka viññāṇa”; but if we generate abhisaṅkhāra, it can become a “kamma viññāṇa” too.

▪That is a brief description of rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, and viññāṇa arising with each sensory event.

▪Then a record of that sensory event gets recorded in the “viññāṇa dhātu.” That record is a “namagotta.” If abhisaṅkhāra were involved, that record would also be associated with kammic energy, i.e., a “kamma bīja” can bring vipāka in the future.

▪This is a complex but fascinating process.

▪As we can see, the accumulation of the five aggregates will stop only at the death of an Arahant. Since there is no rebirth, no more “internal rūpa” to make sensory experiences! That may sound alarming, but remember that each birth only leads to suffering, and most rebirths have unimaginable suffering.

One Type of Consciousness (Vipāka Viññāṇa) Arises With an Ārammaṇa

4. We think of the mind as our own and are always present. But in reality, our consciousness arises based on two conditions.

▪First, we must be awake. If someone is unconscious, no matter how loud we talk, he will not hear. No matter how hard we shake him, he will not feel. When unconscious (or in a deep sleep), our physical bodies shut down. Even though the “mental body/gandhabba” never sleeps, it is not getting any sensory inputs from the brain.

▪Second, one of our six senses must be stimulated by an external sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, or memory. The first five come through our five physical senses, and the sixth is the thoughts that come to our mind via the mana indriya in the brain; see “Brain – Interface between Mind and Body.”

▪An “external trigger” that initiates a new consciousness is called an ārammaṇa. Such an ārammaṇa comes to the mind via one of the “five physical doors” or directly to the mind. Then one of the six consciousness (viññāṇa) arise. These are vipāka viññāṇa. They just come in due to prior kamma, as kamma vipāka.

▪These types of vipāka viññāṇa arise via, for example, “Cakkhuñca paṭicca rūpe ca uppajjati cakkhu viññāṇaṁ.” See, “Contact Between Āyatana Leads to Vipāka Viññāṇa.”

Second Type of Consciousness (Kamma Viññāṇa) May Arise Based on an Ārammaṇa

5. If that external “thought object” or “ārammaṇa” is interesting, we start generating CONSCIOUS THOUGHTS about that ārammaṇa.

▪At this point, our consciousness switches to a new type called a kamma viññāṇa. This new consciousness is more than mere “consciousness” or “awareness.” We are interested in pursuing what we have seen, heard, tasted, etc.. and “getting more of those we liked.”

▪For example, a friend may offer a piece of cake, and the taste of that cake is a vipāka viññāṇa. But if we liked the taste of that cake, we may want to taste it again in the future. We may start thinking about buying or making it and asking that friend how to pursue those two possibilities. That future expectation is in the new type of kamma viññāṇa generated via “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra.”

▪In other words, now we have gone beyond “just experiencing the taste of the cake” or the “vipāka viññāṇa.” Now we have a future expectation to taste it again with a “kamma viññāṇa” generated via our conscious thoughts (vacī saṅkhāra.)

▪Stated in another way, we have initiated a Paṭicca Samuppāda process with “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” and “saṅkhāra paccayā viññāṇa.” That viññāṇa is a kamma viññāṇa.

A Living Being – Body With a Mind Interacting With the External World

6. What we discussed above in summary form is what our lives are all about. We have a physical body and an invisible “mental body/gandhabba” with the “seat of the mind” (hadaya vatthu.) The physical body gets sensory inputs from the external world. Those are processed by the brain and passed to the “mental body/gandhabba.” It is the hadaya vatthu (we casually call the “mind”) that “feels/experiences” such sensory inputs. Then we (our minds) pursue those sensory inputs we like and try to avoid those we do not like.

▪In that process, we create new kamma that leads to the arising of a new body when the current body dies.

▪Of course, the types of bodies that arise in future lives depend on the types of kamma that we do, based on those sensory experiences. If one kills another person to acquire that person’s wealth, one will be reborn in a bad realm (apāyā.) If one generates compassionate thoughts about hungry people and offers them food, one may be reborn in a good realm.

▪That is how the rebirth process continues.

Rūpa Versus Rūpakkhandha

7. The Buddha included all types of matter encountered at any time in one giant “collection” or “aggregate.” That is the “rūpa aggregate” or “rūpa khandha” or “rūpakkhandha.”

▪That means what is in the rūpakkhandha is not real (physical) rūpa. Whatever is observed becomes a mental imprint or a “memory record” moments after observation. See the next post in the series: “Difference Between Physical Rūpa and Rūpakkhandha.”

▪The Buddha divided the mind or “mental aspects” into four categories: vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, and viññāṇa. These entities arise and fade, but a record of them exists (going back to an untraceable beginning.) Those “collections” or “aggregates” are vedanākkhandha, saññākkhandha, saṅkhārakkhandha, and viññāṇakkhandha.

Rūpakkhandha Is Not Stored Directly

8. It is critical to realize that a “rūpa” cannot be stored in the viññāṇa dhātu. Only a “mental imprint” of a rūpa gets stored. That “mental imprint” is in the four “mental aggregates.” Let us briefly discuss that.

▪When we see an object, its shape, colors, etc, are perceived by the mind with the saññā aggregate. Our feelings about it are in the vedanā aggregate, and any action we took is in the saṅkhāra aggregate. Finally, our expectations for such rūpa are in the viññāṇa aggregate.

▪That process is discussed in detail in “Where Are Memories “Stored”? – Connection to Pañcakkhandha” and “Where Are Memories Stored? – Viññāṇa Dhātu” (Ref. 1 in the above chart). However, a good grasp of the concept of the five aggregates is needed as explained in “The Five Aggregates (Pañcakkhandha)” and “Paṭicca Samuppāda During a Lifetime.”

The Five Aggregates Describe any “Living Being”

9. As we will see, a sentient being’s entire existence (through uncountable rebirths) and experiences can be described entirely with those five aggregates. The Buddha showed that those five entities arise and fade away in a manner fully explained in terms of causes and their effect. There is no hidden “soul” or an “ātman.”

▪However, at any given time, there is a “person” with a set of gati (habits/character) responsible for the actions done at that time. It is not an automated process. That is why we cannot say there is no ‘self’ up to the Arahant stage. There is a “self” doing things on his/her own. Of course, only until seeing the futility of such “doings” or “(abhi)saṅkhāra.”

▪That last bullet point is what we need to understand. This time, we will discuss that systematically with a slightly different approach in the new series “Buddhism – In Charts.” However, this series is only a systematic way to arrange previously published posts, while making connections among posts in different sections. It is imperative to read the posts linked above. Buddha Dhamma is deeper than the deepest ocean. One can go into it as deeply as one wants, provided one is willing to spend the time. But what we discuss will be essential parts.

Summary

10. We have laid the framework to examine the conscious life and the rebirth process based on the five aggregates or pañcakkhandha. Please read and understand the whole section on “The Five Aggregates (Pañcakkhandha).” I will discuss memory formation, storage, and extraction in the next post before we connect it all to Paṭicca Samuppāda.

▪In this analysis, the whole world is divided into just five categories. One is the rūpa aggregate, the “collection of MEMORIES of all rūpa” or the rūpakkhandha. That includes memories of all “material objects,” including our physical bodies and all external objects one has seen in all previous lives. We will discuss that in the next post.

▪The other four aggregates or “heaps” or “collections” of four types of mental entities: vedanā (feelings), saññā (perception), saṅkhāra (thoughts of speech and actions), and viññāṇa (vipāka viññāṇa or kamma viññāṇa.)

▪I have discussed this topic in detail in “Paṭicca Samuppāda During a Lifetime.”

Reference

1. “Where Are Memories “Stored”? – Connection to Pañcakkhandha” and “Where Are Memories Stored? – Viññāṇa Dhātu.”