July 20, 2024; rewritten March 22, 2025 (revised #7 same day)

Āhāra in Buddha Dhamma refers to “food” for the mental body, not the physical body.

Āhāra Means “Mental Food”

1. As discussed on this website, a human has two bodies: physical and mental. The “mental body” (manomaya kāya or gandhabba) is where thoughts arise; it is made of a few Suddhaṭṭhaka, the smallest unit of matter in Buddha Dhamma; see “The Origin of Matter – Suddhaṭṭhaka.” In the suttās, the physical body is called “cātumahābhūtikassa kāya” or the “body made up of the four great elements of pathavi, āpo, tejo, vāyo; see, for example, “WebLink: suttacentral: Assutavā Sutta (SN 12.61).” In some Commentaries it is referred to as “karaja kāya.”

▪Both these bodies need food to survive.

▪We eat physical food (like bread, rice, etc.) to sustain our physical bodies, but the Buddha did not teach about those foods.

▪Buddha’s teachings are all about the mind. A mind attaches to “pleasurable things in this world” and consumes four types of food to live. The consumption of āhāra stops only when all ten sansāric bonds (saṁyojana) are eliminated.

▪A special category of food called “kabaḷīkārā āhāra” is available only in kāma loka. Three more types of foods are needed in all three lokās (kāma, rūpa, and arūpa loka). They are (saŋ)phassa, mano sañcetanā, and viññāṇa āhāra. See “WebLink: suttacentral: Āhāra Sutta (SN 12.11).” Brahmās in 20 Brahma realms have only the “mental body,” and their minds only consume the latter three types of āhāra.

▪Therefore, the mental body of a human (human gandhabba) consumes all four types of food. In the suttās, āhāra NEVER refers to food for the physical body.

Nibbāna = Cessation of All Four Āhāra

2. All four āhāra to the mental body stop when one becomes an Arahant, i.e., when attaining Nibbāna; see “WebLink: suttacentral: Āhāra Sutta (SN 12.11).”

▪However, the mental body of the Arahant can live without āhāra until the death of the physical body. Thus, with the death of the physical body, the mental body also dies, and the Arahant attains Parinibbāna (“full Nibbāna”) at that point.

▪Food is essential for all living beings. If one stops eating physical food (including water) for about seven days or so, one’s physical body will die.

▪However, a puthujjana’s mental body (gandhabba) will not die with the physical body. It comes out of the dead physical body and lives in “gandhabba loka” until pulled into a womb to be born again with a physical body.

▪A human gandhabba also has a finite lifetime. It also dies at the end of its lifetime, but another mental body (associated with one of the 31 realms) will immediately be created by the kammic energy associated with that lifestream. See “What Reincarnates? – Concept of a Lifestream.”

Nibbāna and Parinibbāna

3. Even though all four āhāra to the mental body cease when one becomes an Arahant, his/her mental body (gandhabba) cannot die as long as it is attached to a living physical body.

▪At the death of the physical body, Arahant’s gandhabba comes out of the dead body. Now, it must be sustained by one or more of the āhāra. Since all four āhāra have ceased, it will die at that instant.

▪In other words, even if Arahant’s gandhabba had not reached the end of its life, it would die instantly at the death of the physical body. Unlike the physical body, the subtle mental body cannot survive even a moment without food (once it is separated from the physical body).

▪Now the question is: “Why doesn’t the Arahant’s mind grasp another mental body (i.e., another existence) at that moment (like for other beings)”? That process is called “cuti-paṭisandhi,” where cuti is the death of one mental body, and paṭisandhi is the grasping of another. Paṭisandhi (“paṭi” is to “bind,” and “sandhi” is a “joint” in Pāli or Sinhala.) Thus, paṭisandhi means joining a new life at the end of the old. That happens a thought-moment after the last citta of the current existence (bhava.)

4. Two conditions must be satisfied to generate a new mental body at the cuti-paṭisandhi moment: (i) There must be a kamma bījā available to grasp, and (ii) One’s mind must willingly grasp that kamma bījā.

▪We all have accumulated numerous kamma bījā even in previous lives, so the first condition is always satisfied for anyone. Therefore, the second condition — grasping a new existence (bhava) at the cuti-paṭisandhi moment — is the condition that stops the rebirth process.

▪With each stage of magga phala, the possibility of grasping another existence decreases as the number of sansāric bonds (saṁyojana) are eliminated. For example, a Sotāpanna’s mind will not grasp a bhava (existence) in the apāyās with the removal of the first three saṁyojana; A Sakadāgāmi’s mind will not grasp human existence. In addition, an Anāgāmi will not grasp any bhava in the kāma loka with the removal of the first five saṁyojana, and an Arahant (with all ten saṁyojana eliminated) will not grasp any existence in any realm.

▪The saṁyojanās are broken at each stage as follows: Sotāpanna (3), Anāgāmi (2), and Arahant (5). See “Dasa Saṁyojana – Bonds in Rebirth Process.” They can broken only via cultivating paññā (wisdom).

5. An excellent example from the Tipiṭaka is Ven. Aṅgulimāla. He killed almost a thousand people and had accumulated enough strong kamma bījā (in that last life itself) to be reborn in an apāya.

▪Just after meeting the Buddha, he attained the Sotāpanna stage. At that moment, the possibility of rebirth in an apāya was removed with the breaking of the first three saṁyojana.

▪After several months, he attained Arahanthood, and all ten saṁyojana were eliminated; thus, he was not reborn in any realm when his physical body died.

▪See “Account of Aṅgulimāla – Many Insights to Buddha Dhamma.”

Weakening and Elimination of Āhāra With Magga Phala

6. All four types of āhāra intake weaken at each stage of magga phala.

▪For example, “kabaḷīkārā āhāra” is responsible for generating kāma rāga. It is weakened at the Sotāpanna and Sakadāgāmi stages and eliminated at the Anāgāmi stage. As we can see, removing the kāma rāga saṁyojana is the same as stopping the intake of kabaḷīkārā āhāra. Note that a Sotāpanna only eliminates the three diṭṭhi saṁyojana, but that weakens the kāma rāga (and paṭigha) saṁyojanās.

▪The remaining three types of āhāra (samphassa, mano sañcetanā, and viññāṇa āhāra) also weaken with each stage of magga phala. However, they are eliminated only at the Arahant phala with the breaking of the remaining five saṁyojanās.

▪Thus, the “lifestream” for an Arahant in this world of 31 realms ends with the death of the physical body. See “What Reincarnates? – Concept of a Lifestream”

Kabaḷīkārā Āhāra – Only in Kāma Loka

7. Sensual pleasures with “close contacts” of smell, taste, and bodily contacts (touch, especially sex) are available only in the realms of kāma loka. Kabaḷīkārā āhāra is closely associated with the six types of “kāma guṇa” available in kāma loka. See “Kāma Guṇa – Origin of Attachment (Taṇhā).”

▪Kabaḷīkārā āhāra means craving for mind-pleasing odors, tastes, and body touches (including sex).

▪Rūpāvacara Brahmās in “rūpa loka” experience only two of the five physical senses (sight and sound), and they have “rūpa rāga” (and mainly crave “jhānic pleasures.”)

▪Arūpāvacara Brahmās in “arūpa loka” do not experience the five physical senses. They only have the mind or mano (sensing dhammā) and have only “arūpa rāga“ (and mainly crave “arūpa samāpatti pleasures.”)

▪Therefore, kabaḷīkārā āhāra is the strongest because it triggers the accumulation of “apāyagāmi kamma,” leading to rebirth in the apāyās. This is why the “nava kamma” stage is absent in the rūpa and arūpa Brahma realms.

▪For details, see “Kāma Rāga, Rūpa Rāga and Arūpa Rāga.”

Paṭicca Samuppāda Does Not Start Without Āhāra

8. There is yet another way to look at this mechanism of grasping a new bhava at the cuti-paṭisandhi moment. In the uppatti Paṭicca Samuppāda (PS) cycle, a certain bhava is grasped at “upādāna paccayā bhava.”

▪When we trace the cycle backward, we see that PS starts at “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” and “saṅkhāra paccayā viññāṇa.” (Abhi)saṅkhāra generation starts at the “purāṇa kamma” stage unconsciously, but potent kammic energies that can bring more rebirths occurs only in the “nava kamma” stage with the conscious accumulation of kāya, vacī, and mano kamma.

▪Cessation of all four types of āhāra means the cessation of avijjā and thus the cessation of all subsequent terms in Paṭicca Samuppāda: (abhi)saṅkhāra, (kamma)viññāṇa, nāmarūpa, salāyatana, (saŋ)phassa, (samphassa-jā-)vedanā, taṇhā, upādāna, bhava, jāti, and soka, parideva, …(“the whole mass of suffering.”)

▪No Paṭicca Samuppāda cycle can be active for an Arahant. Thus, at the cuti-paṭisandhi moment, it cannot grasp any existence in this world.

Two Critical Roles of Viññāṇa

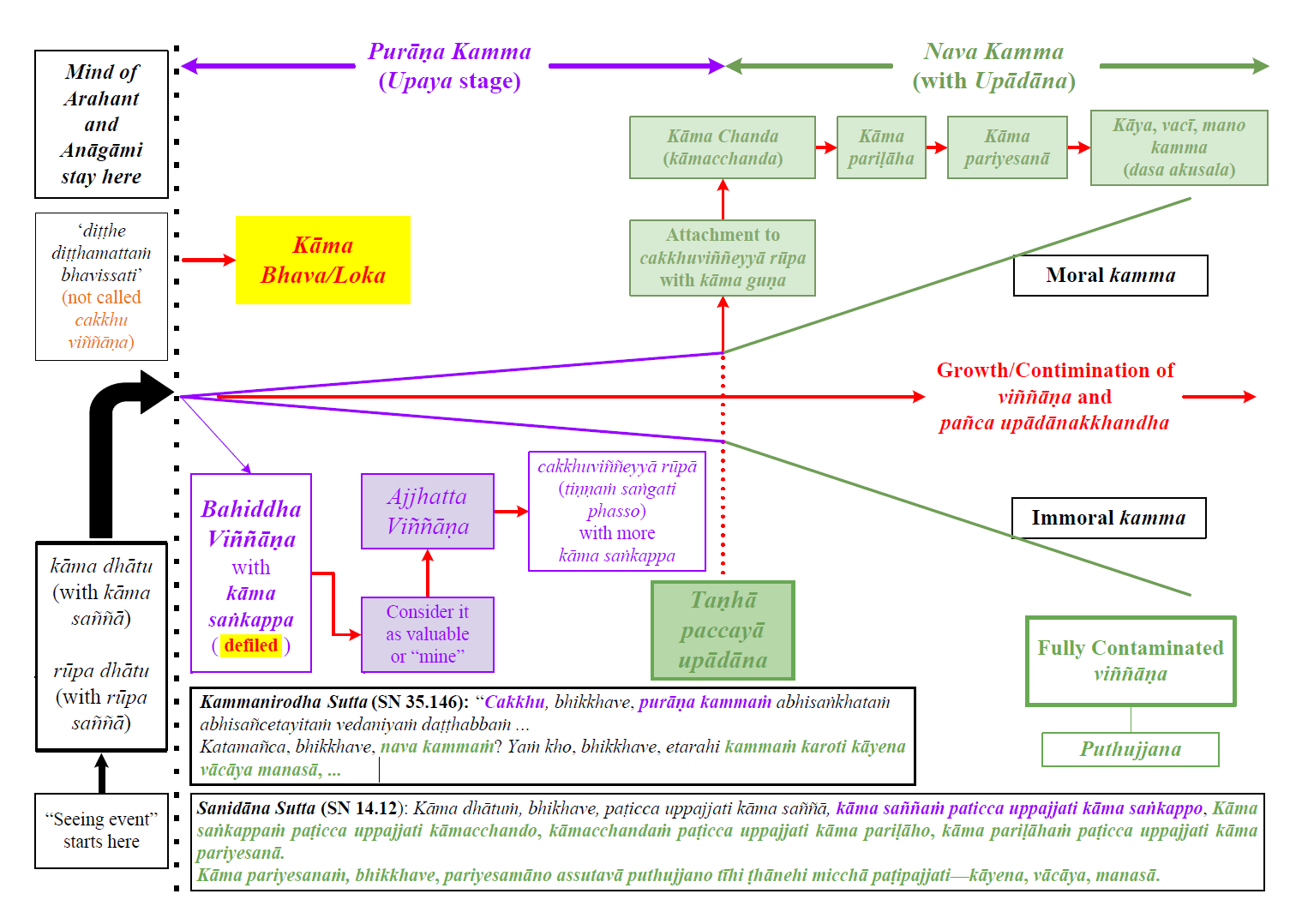

9. Therefore, the word viññāṇa represents much more than just consciousness. Even a “vipāka viññāṇa” (which is bahiddha viññāṇa; see “Purāṇa and Nava Kamma – Sequence of Kamma Generation”) is defiled. That happens automatically due to unbroken saṁyojana. For example, a puthujjana’s mind will automatically get to the bahiddha viññāṇa in the “purāṇa kamma” stage. On the other hand, the mind of an Arahant will stay in kāma dhātu, as indicated in the chart below (taken from the above post).

Download/Print: “WebLink: PDF file download: Purāṇa and Nava Kamma -2-revision 3”

▪A “seeing event” for an Arahant is not called a cakkhu viññāṇa. It is called “diṭṭhe diṭṭhamattaṁ bhavissati” or “seeing without rāga, dosa, moha arising in mind.” This critical point is discussed in detail in the above link.

10. “Viññāṇa” is one of the four “foods” (viññāṇa āhāra) for accumulating new kamma bījā and also provides “food” or “fuel” for grasping a new existence (bhava.)

▪Viññāṇa is the opposite of ñāṇa (pronounced “gñāna”) or wisdom. When one cultivates ñāṇa, one’s avijjā is reduced, and certain types of viññāṇa are concomitantly reduced.

▪Pronunciation of viññāṇa:

WebLink: Listen to the pronunciation of “viññāṇa”.

▪Pronunciation of ñāṇa:

WebLink: Listen to the pronunciation of “ñāṇa”.

▪As one attains the four stages of Nibbāna, avijjā is removed in four stages, and the strength of viññāṇa is accordingly reduced. Viññāṇa manifests until all ten saṁyojana are removed from the mind at the Arahant stage. After that, “seeing” and “hearing” are not called “cakkhu viññāṇa” and “sota viññāṇa”, but “diṭṭhe diṭṭhamattaṁ bhavissati and sute sutamattaṁ bhavissati.” See “Purāṇa and Nava Kamma – Sequence of Kamma Generation.”

▪This pure level of consciousness — without any defilements and thus any cravings — is called pabhassara citta; see “Uncovering the Suffering-Free (Pabhassara) Mind” and “Pabhassara Citta, Radiant Mind, and Bhavaṅga.”

▪In other words, an Arahant can experience the world with a purified mind that is not blemished by even a trace of greed, hate, or ignorance. Therefore, at death, his purified mind will not grasp an existence (bhava).

Viññāṇa Āhāra = Nāmarūpa Formation

11. As long as a mind generates nāmarūpa, the expectation of a worldly outcome remains with the mind, and one will be born somewhere in the 31 realms. This is an advanced subject; see “Nāmarūpa Formation.” This is why viññāṇa is called a type of food for the mental body.

▪As one proceeds at successive stages of Nibbāna, one will crave fewer and fewer things in this world. For example, at the Anāgāmi stage, one would have lost all cravings for sensual pleasures — removing a big chunk of nāmarūpa formation.

Sañcetanā Āhāra = Defiled Cetanā

12. Kamma viññāṇa is cultivated by thinking, speaking, and acting in such a manner. Thinking, speaking, and acting are done based on mano, vacī, and kāya saṅkhāra which arise due to sañcetanā (“saŋ” + “cetanā” or defiled intentions; cetanā is pronounced “chethanā”).

▪For example, an alcoholic regularly thinks about drinking, likes to speak about it, and likes to drink. The more he does those, the more that kamma viññāṇa will grow.

▪It is easy to see how a gambler, smoker, etc, grow their corresponding viññāṇa the same way.

▪The ability to generate such viññāṇa can lead to other immoral activities, such as the tendency to lie, steal, and even murder.

▪Therefore, all activities done in cultivating such viññāṇa are based on mano sañcetanā. That is why mano sañcetanā are also food for the mental body.

Phassa Āhāra = Samphassa Āhāra

13. The triggers for such sañcetanā are defiled sensory contacts or samphassa. These are not mere sensory contacts but those arising with “saŋ” (rāga, dosa, moha), i.e., with “defiled intentions.” It gives rise to “samphassa-jā-vedanā.”

▪The distinction between phassa and samphassa is explicitly made in Abhidhamma. However, in suttās, “phassa” almost always refers to “samphassa” and never refers to “mere sensory contact.” As we have discussed, Abhidhamma was not developed at the time of the Buddha; he summarized Abhidhamma theory to Ven. Sāriputta, and it took over 200 years for the bhikkhus of “Sāriputta lineage” to finalize the “Abhidhamma Piṭaka.” See, “Abhidhamma – Introduction.”

▪When one looks at something, thoughts arise via phassa. But if one looks at it with greed or hate (and ignorance) in mind, that is samphassa (“saŋ” + “phassa,” which rhymes like “samphassa”); see, “Vedanā (Feelings) Arise in Two Ways.”

▪This is why defiled sensory contacts or samphassa are food for the mental body. Such sensory contact can lead to thoughts about immoral actions and give rise to future kammaja kāya.

▪Therefore, one must avoid sensory contact with sense objects that one has taṇhā for. We need to remember that taṇhā is attachment to something via greed or hate; see “Taṇhā – How We Attach Via Greed, Hate, and Ignorance.”

▪So, it is a bad idea for a gambler to visit casinos, an alcoholic to make visits to bars, etc. Furthermore, one needs to avoid friends who encourage such activities, too.

▪It is best to avoid any “defiled contact” (samphassa) that can lead to sense exposures that provide “food” for the mental body, i.e., get us started thinking about those destructive/immoral activities.

14. Now we can see how those three types of food act in sequence to feed the mental body: Defiled sensory contacts (samphassa) can lead to mano sañcetanā, which in turn cultivates viññāṇa. That happens even in the “purāṇa kamma” stage with the (unconscious) abhisaṅkhāra generation.

▪Abhisaṅkhāra generated only with mano saṅkhāra does not lead to potent kamma that can bring rebirth.

▪In the “nava kamma” stage, the abhisaṅkhāra generation occurs for defiled speech and bodily actions. Those are the potent kamma that can bring rebirth.

▪In other words, samphassa automatically starts mano abhisaṅkhāra; then, we start thinking and speaking with a defiled mind, i.e., we start vacī abhisaṅkhāra (consciously generating defiled speech). Then, when the feelings get strong, we will start doing immoral deeds (with kāya abhisaṅkhāra).

▪It is essential to realize that mano abhisaṅkhāra, vacī abhisaṅkhāra, and kāya abhisaṅkhāra are all generated in the mind: vacī abhisaṅkhāra are conscious defiled thoughts that can lead to immoral speech; kāya saṅkhāra are conscious defiled thoughts that move the physical body for immoral deeds.

▪All three types of saṅkhāra arise due to mano sañcetanā. We cannot think, speak, or do things without generating appropriate mano sañcetanā.

Mental Body (Gandhabba) Is Primary

15. As we have discussed, the physical body is just a shell controlled by the mental body (gandhabba). See “Manomaya Kāya (Gandhabba) and the Physical Body.”

▪Sensory contacts come through the physical body, are processed by the brain, and passed onto the mental body where samphassa occurs. When the mind (in the gandhabba) attaches to samphassa (defiled contacts), it generates mano sañcetanā and thinks, speaks, and acts accordingly, developing various types of viññāṇa.

▪It is kabaḷīkārā āhāra (available only in kāma loka) that triggers a mind to engage in accumulating the worst types of kamma by speech and the physical body; thus, they occur only in kāma loka. However, the other three types of āhāra must trigger all attachments present in all three lokās.

▪That is why all four types of food are for the mental body.